The unidentified in the country of 100,000 disappeared

Violence is not the only cause of death among the 52,000 bodies of unidentified persons in Mexico: a myriad of causes, from illness and accident to even extraordinary conditions. Their clothes also tell the story of their absence. The people who wore those blouses, those pants, those sweatshirts can still be counted on Mexico’s official list of more than 100,000 disappeared persons.

By VIoleta Santiago / Pictures: Fred Ramos

May 30, 2022

The grey sweatshirt has blood on the chest. The background is perfectly white, but a large stain spreads at the level of the heart, and another smaller one, in the right armpit. Different parts of the hood are also splattered with six spots of blood. But, what photographer Fred Ramos noticed the most is not the stain, darkening in Chihuahua’s Medical Forensics Service (Semefo), but the brown packing tape wound tightly around the right wrist.

As Ramos looks at the image in his computer in a Mexico City coffee shop, he ventures a possible story that the bloodied clothing tells in silence. “We don’t know anything more than what we’re seeing. That is, I come to conclusions like, maybe they had this girl tied up with tape, but who knows what really happened? Because not even the authorities are saying. We don’t know who she is.”

The piece of clothing that photographer Ramos took in the Chihuahua City forensics lab of the State Prosecutor’s Office is one of the few vestiges that accompany an unidentified body in Mexico, one of the more than 52,000 documented by the Movement for Our Disappeared in the morgues or potter’s fields in the whole country. Among them may be some of the more than 100,000 disappeared and non-located persons the Mexican government admits to.

Clothing of an unidentified person in the forensics lab of the Chihuahua State Prosecutor’s Office

Gender: female

Age: Between 14 and 16 years old

Date found: October 27, 2017

Location: Kilometer 100, Chihuahua-Ciudad Juárez highway

Cause of death: Gunshot wound

The photo was taken June 22, 2021. The file has sparce data. The authorities only know that it belonged to a teenager between the ages of fourteen and sixteen, found dead October 27, 2017, at kilometer 100 of the highway between the city of Chihuahua and Ciudad Juárez, and that she died from a gunshot wound.

On May 17, 2022, Mexico surpassed the tragic figure of 100,000 disappeared persons. To that figure, we can add 135,500 who were once missing but were found alive, and another 9,900 who were found, but dead. The figures show a limbo between life and death, between the crisis of the disappearances and the coroner. The families looking for their loved ones scour the labyrinths of the death archives, where they see photographs of bloody clothing and bodies that have been dismembered, tied up, and tortured.

The crisis of the disappearances grew sharply starting in 2006, after then-President Felipe Calderón declared the so-called “war on drugs.” The numbers soon surpassed the lists of disappeared by the state during the “dirty war” of the last century, which came to 920.

The violence affects different parts of the country differently. Culiacán and Ciudad Juárez, for example, head the list of the municipalities where the most missing persons were found dead. By state, Tlaxcala, Sinaloa, Guerrero, Chihuahua, and Baja California Sur concentrate the highest percentages of persons found dead vis-à-vis the total number reported missing.

The tragedy is not limited to the number of persons disappeared in recent decades. At the same time, thousands of bodies have been discovered in clandestine mass graves, above all by collectives dedicated to searching for the disappeared. And these bodies ended up accumulating in forensic labs and potter’s fields when the institutions did not have the ability to deal with them.

Photographer Fred Ramos is from El Salvador and began his work as a reporter at El Faro. In the capital of Chihuahua state, he replicated a project he had already carried out in his country of origin: photographing the clothing worn by disappeared persons found dead and housed in a morgue, waiting to be claimed or for an anonymous grave.

He photographed twenty-four pieces of clothing that some of the unidentified persons in central Chihuahua wore for the last time, and he noticed something important: the variety of causes of death and their relationship to the clothing.

Clothing of an unidentified person in the forensics lab of the Chihuahua State Prosecutor’s Office

Gender: female

Age: Between 25 and 35 years old

Date found: June 16, 2020

Location: Las Moras Avenue and Delicias Street, Chihuahua

Cause of death: suicide

For example, a light blue pair of jeans with blood and dirt on the back pockets, worn by a man of between thirty-five and forty years of age, found dead from natural causes on July 18, 2020, on a street in the Pacífico Neighborhood. Or blue pants and t-shirt with a stain that looks like rust, that starts at the abdomen, goes down through the groin, and ends at the ankles. This was worn by a woman between twenty-five and thirty-five, found June 16, 2020. The cause of death: suicide.

One person drowned, deaths from overdoses, people run over or murdered with guns or knives or from beatings, or even those whose causes of death are unknown. What Ramos found was actually the reflection of the variety of causes of deaths of tens of thousands of people in forensic labs or potter’s fields in municipal cemeteries.

A mosaic that is evidence of the multiple forms of violence, but also of other possible ways of losing your life: not everything is gunshots and rivers of blood. The logs also show an abundance of “no data” and “not systematized.” And they show that dying unidentified in Mexico is more complicated and more common that one might think.

Death beyond violence

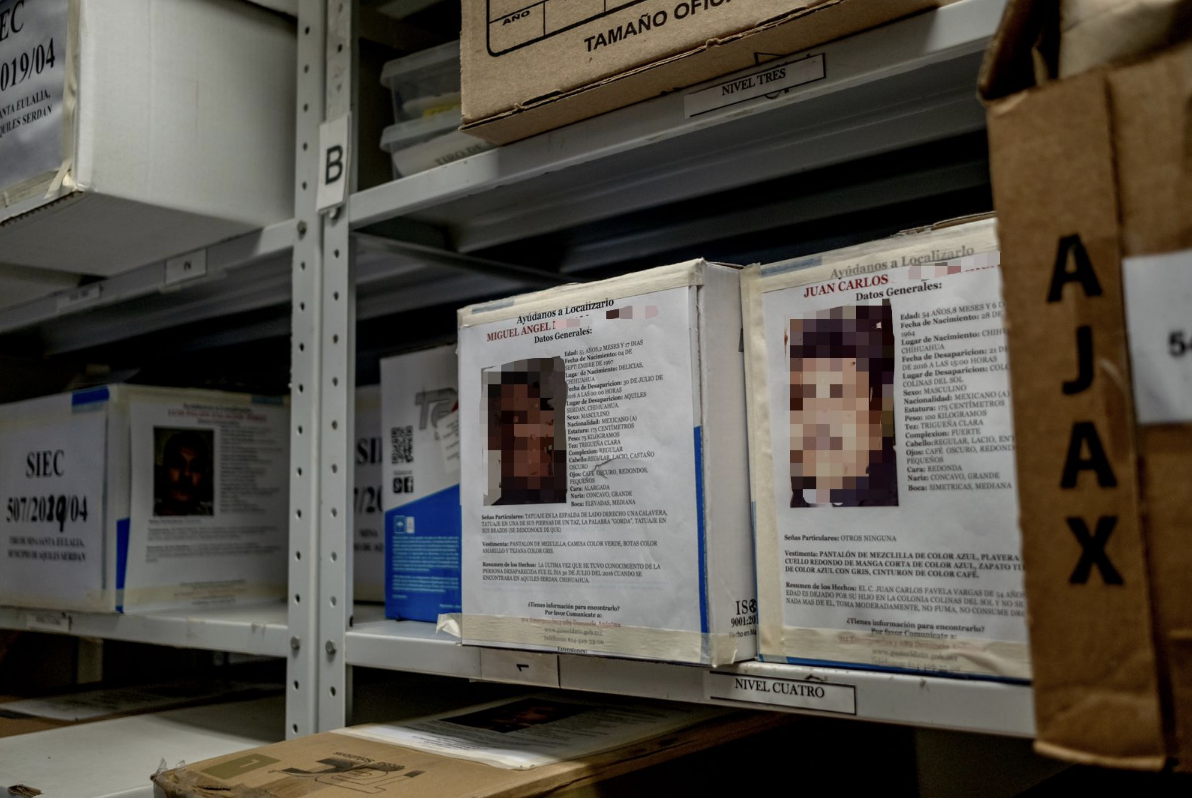

In the anthropology area of the Chihuahua Office for Technical Expertise and Forensic Sciences, what a person means is reduced to something as small as a box. The white cardboard boxes arranged on long grey shelves can be told apart by the faces and strips of paper with information from the search logs pasted on them and each one’s siec code.

The Cadaver Admittance and Release System (siec) is a forensics deposit logging program that has been up and running for more than a decade, much before the protocols developed by state and federal prosecutors and authorities began operating, as the Semefo authorities the Ramos visited told him.

“They use the code to look each one up in the system and they told me, ‘Ah, okay. He was found on such-and-such a date, in such-and-such a place; he’s a male of approximately this age.’”

Absence is something quite complicated to document visually, says Ramos. But he trusts that the clothing of the unidentified persons can help construct its own story —in addition to the possibility that someone might recognize it.

Ramos obtained permission to take photographs in Chihuahua while the forensic scientists made their own catalogue of clothing, and he constantly asked himself questions about the clothing he was seeing and the causes he read. Drowning, for example. At first glance, the wrinkled clothing (yellow short-sleeved t-shirt; dark jeans) was worn and dirty, but they also had two red circles.

“I’d like to know if it could have been an accidental drowning or because somebody held his head down. Those are very different, right? But they didn’t know. They said, ‘No, no. We don’t know. We’d have to talk to I-don’t-know-who.’ But really, I think they didn’t have any more information than that, even though they boasted of their system being very orderly and being a little more advanced than other states in Mexico.”

Skeletal remains stored at the Forensic Anthropology department of Chihuahua Photo: Fred Ramos

The data base that Quinto Elemento Lab put together for the #CrisisForense research project in 2020 incudes the record of 38,891 bodies; that includes dozens of drowning cases, and in some cases, it specifies whether it was in salt or fresh water.

Every possible cause is listed. However, the record is not systematic. Many states list the cause of death as “suicide” in general, while others specify: “suicide by hanging.”

The lack of order can also be seen in causes such as anoxemia (lack of oxygen): by immersion (drowning), from suffocating in a well, from obstruction, by bronchoaspiration (of blood or objects), fetal death, strangulation, inhalation of solvents, or even being buried alive.

Hundreds of records explicitly show the cause of death as “murder” or “violent death” (without further information), while others are catalogued under “firearm,” “decapitation,” “dismemberment,” or “burned to death.”

However, sometimes, the dividing line between knowing if it was a violent death or a death from illness is so fine that the additional information can help to better understand the context of the death. For example, the records for anemia (loss of hemoglobin): among some cases of malnutrition, many refer to hemorrhages from different parts of the body, whether because of traffic accidents, gunshot wounds, or ulcers.

Aside from violence, other prevalent causes of death are traffic accidents (crashes or pedestrians being run over) and even falls from a train or being hit by a train. In Mexico City, at least eighty-nine unidentified people lost their lives on the subway train tracks; most of them are males who ended up in potter’s fields. Other common causes of death, more or less in equal numbers, are homicide, natural causes, or accidents.

Illnesses and organ failure are also frequent in almost all the states: cirrhosis, heart attacks, tuberculosis, septic shock, cancer, thrombosis, and swelling. Other causes of death are more characteristic in certain areas of the country: Sonora has logged the largest number of unidentified people who died of dehydration (severe dehydration, heatstroke), but Tamaulipas and Puebla have also logged cases of death from underlying diseases.

Nationwide, Yucatán stands out because it does not include a cause of death on many files; instead, it indicates missing teeth. In a couple of cases in Sonora, under the cause of death, the technician has written “under a tree” or “under a bridge.” Chihuahua is the only state, with eighty-three cases, that calls the cause of death “drug abuse,” while Durango and Sonora use the term “overdose.”

It’s completely common. Among the 38,000 unidentified bodies that the Quinto Elemento Lab documented until 2019, in at least 21,818 cases, the authorities have not determined a cause of death; they use terms such as “cause of death under study,” “causes unknown,” “skeletal remains,” or “no data.” In Sonora, the State of Mexico, Veracruz, Sinaloa, San Luis Potosí, Puebla, Oaxaca, Hidalgo, Durango, Colima, and Coahuila some bodies are logged in without a corresponding cause of death. However, the extreme cases are Querétaro, Tabasco, Nayarit, Morelos, Michoacán, Jalisco, Guerrero, Guanajuato, and Baja California, where practically all the data bases requested by the public information transparency unit showed no cause of death at all.

“These data bases are often rudimentary, incomplete, and not particularly up to date,” says the “La crisis forense en México” (The Forensics Crisis in Mexico) report, written by the For Our Disappeared Mexico Movement.

Precision about the cause of death depends on the state of the body: the simplest way to discover it is through an autopsy. But a funeral home worker in southern Veracruz explained that in those states, people “work in the old-fashioned way.” Without enough medical forensics offices with refrigerated chambers or forensic equipment, private funeral homes make up the difference in infrastructure. So, with daytime temperatures of up to forty degrees Centigrade, “they work with their eyes and their hands, à la Mexican, without equipment.” And without that, determining a person’s cause of death becomes very complicated, with a very high margin of error.

When flesh decomposes and only the bones are left, knowing the causes of death of an unidentified body becomes a valuable piece of information. Not only does it allow the authorities to know, from the start, whether it was a violent death, an accident, or a death due to disease, but the causes of death are also linked to a date. If other details such as the clothing, for example, can be added, this can help form an idea of how, when, and where the person died.

The problem comes when the log is wrong and the causes on paper do not coincide with what the eye can see. Virginia Garay Cázares, a searcher from Nayarit and a member of the National Citizen’s Council, explains that they have found mistakes in the data base descriptions. One of the most serious that she remembers is, “In a description, they put down natural causes, but when we look at the skull, it has the famous coup de grâce.”

“We no longer know what to think about it. We don’t believe it. Many mothers are told that there’s their loved one, and they often ask for a review. It’s not that thy don’t want to accept it. So many things have happened that the truth is, we families just don’t trust [what we’re told],” adds Virginia, who has been looking for her son Bryan Eduardo Arias Garay since February 6, 2018, when he disappeared in Tepic, Nayarit.

The problem is that a bad description of the physical characteristics of a body or of its cause of death means that the possibilities of identifying the person you are looking for are reduced. Garay explains that they have recovered bodies that for years were categorized as unidentified and were being stored under the authority of forensic authorities, even though their relatives reported them missing, and for that entire time, those relatives went out to search, to dig, to put up fliers, and to march.

“The catalogue of the photographs of bodies has a brief description, such as ‘body without a skull,’ and when you actually look at it, the skull is there. They showed the photo of the skeleton, and it was a body. They said it was a female body and the clothing is a man’s. Then they say, ‘unidentified sex.’ They’re not doing their work the way they should,” says Garay.

In the face of what they classify as “bad practices,” the women searchers have decided to identify the bodies themselves and to observe all the possible indications, from the clothing to the characteristics that might suggest how the person died, before they are lost in a badly run institutional registry. Rosaura Magaña, the leader of the Between Heaven and Earth collective, based in Jalisco, thinks that the field experience they have has been very useful because, “By now the findings show you the kind of death that has happened by the condition of the bodies.”

“That’s the reason we mistrust,” says Garay.

The forensics crisis, the crisis of identification

Although the Semefo where Fred Ramos worked to document the last clothing worn by unidentified people in Chihuahua looked quite modern, it still had a lugubrious air about it. Above all, this was because of a hallway where clothing was hung out to dry, with traces of fluids or dirt on it, before being vacuum sealed to be sent to the evidence department.

The absence smells like earth and blood. Despite his using a facemask and wearing the expert’s white coat, what Ramos remembers most is the smell. The smell of the corridor and the smell the bags of clothing gave off when opened to be photographed. “These were bags that had been vacuum sealed hours after a person had died in that clothing. Just imagine, there was clothing that was really fresh, despite having been in there two or three years. Those stored-up smells came out as a single one; a really strange mix of odors.”

According to the most recent public report about the Search and Identification of Disappeared Persons, written by the National Commission to Search for Persons, between December 1, 2018, and September 17, 2021, during the administration of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, only four out of every ten bodies exhumated from clandestine graves could be identified, and only three out of every ten were turned over to a family member.

Chihuahua is one of the states with the best systematization of bodies, identified or unidentified. In most of the country, the situation is very different. Rosaura Magaña remembers very well what happened in Jalisco in 2018, when two refrigerator trailer trucks were loaded with 322 bodies that didn’t fit in the morgue; one of the worst episodes of the forensic crisis reflecting the saturation of the labs all over Mexico.

Garay tells the story that in one of the Jalisco trailer-trucks there were a couple of bodies of persons from Nayarit. One of them was that of a young man who had not been reported missing, so the prosecutor’s office had not moved on it any further. “What I did was to take it upon myself to go to the woman’s house. The boy had gone out to work. Two years. I couldn’t believe it. A week later, the woman went and identified the body as her son.”

Magaña is concerned about the future: “The problem continues to exist. The graves of bodies and skeletons increase. When I started [with the searches] in 2017, there were 3,700 disappeared and they couldn’t stop it. Five years later the number had tripled and it’s getting worse. They’re moving ahead at a snail’s pace.”

The situation in Mexico is such that, it doesn’t matter if the cause of death was natural, from disease, an accident, or an act of violence. Most probably, if the body is not identified, it will end up in a potter’s field.

This is very serious for several reasons. Searcher Virginia Garay says, “It’s terrible for a family to know that the body was there for a certain amount of time and the authorities did nothing. That they were sent to the potter’s field and the family has to pay to exhume the bodies.”

“They spend five, ten, fifteen, twenty years looking for their relative thinking that they’re alive and they’re in a grave because the system’s flawed,” says the funeral parlor worker from Veracruz.

Based on her experience in the search collective, Magaña mentions the shock and pain for a family when, because of decomposition, what they receive looks different from what they had originally identified. “We have the experience that they take one or two years [to be identified and handed over]. It’s very traumatic. When they turn over the body, it’s more deteriorated. That’s another kind of revictimization.”

The crisis of unidentified bodies in Mexico complicates things for searchers because not all the unidentified bodies correspond to a report of a disappeared person: the registries include people who have died from disease, accident, or suicide, and who lived alone or whose bodies simply were not claimed, even though the authorities might know their names because they had identification on them, for example. Many possibilities exist.

It’s common to die “identified” and still end up in a potter’s field, says the National Commissioner for the Search for Disappeared Persons in Mexico, Karla Quintana Osuna, and the director of the National Search Commission, Javier Yankelevich.

In the Jalisco “death trailer-trucks,” Garay remembers the case of a Nayarit man who had only one son, but he was in the United States. “I can’t go for him,” he told Virginia. Even with a first and last name, he ended up in the potter’s field.

Quintana and Yankelevich also talk about this other crisis within the forensics crisis: how people end up in potter’s fields who potentially could be identified if the data on their credentials, their clothing, or their tattoos were compared with the data bases of persons reported as disappeared.

The Veracruz funeral parlor worker remembers a particular case. The skeleton of a man was found in a grave in 2014. There was little flesh left on his bones, but the clothing was almost completely intact: dark-colored, blue-and-red striped Lacoste boxer shorts; a white sock with blue and red stripes and a drawing of a soccer ball; a white t-shirt, dirtied by the soil. The remains lay in a corner of the funeral home for almost two years in a black bag, until the prosecutor’s office ordered them to be sent to the potter’s field. In that same city, a dozen disappearances had been reported, but no one cross-checked the data to try to give the person back his/her identity or name.

A report about public cemeteries in the country’s metropolitan areas, written by the National Institute for Geography and Statistics (inegi), in 2020, 10,247 bodies were buried in potter’s fields. Of these, 4,611 were unidentified bodies, but 2,689 were identified, plus 1,404 identified but not claimed. The Valley of Mexico is the area with the largest number of identified bodies in this kind of grave, but others are the cemeteries of Tijuana, Mexicali, Chilpancingo, and Mérida. León, Tijuana, and Puerto Vallarta, and Monterrey head up the list of the most identified, unclaimed bodies.

The Semefos’ data bases and the physical conditions and human resources in these places become the perfect scenario for non-identification. Thus, the accumulation of bodies and the fight over space in the overwhelmed morgues means that the oldest cases are moved toward potter’s fields or universities, that is, toward institutional disappearance.

Thousands of disappeared, thousands of unidentified bodies

Mexico has over 100,000 disappeared persons. It is also the country where collectives point out that more than 52,000 unidentified bodies exist, spread out mostly in potter’s fields, in morgues, in universities (as donations to medical schools), in funeral homes, cremated, or nowhere anyone knows.

“There were lots, lots of boots. The way people dressed was really in the Northern style,” Ramos remembers about his photographic project in Chihuahua. Although the clothing of a person who has been run over is preserved differently from that of a homicide victim, he said he felt they were all people from the region because they used the same kind of footwear.

The causes of death suggested something else to Ramos. The first photo he took for his project is the strangest of all: it’s a light-colored pair of pants, so tattered that they look like they’re about to fall apart at any moment; a cap; and a blanket with red crisscrossed stripes. The photographers thinks that the body was buried wrapped in the blanket, something he had not documented before in his years as a journalist in El Salvador.

“Every time I moved it, a bunch of dirt fell out. I think that photo is the one that speaks to the disappearances in Mexico, of situations very specific to here, that I had never seen in El Salvador.”

What he sees is patience. He remembers the photos he took in his countries, where many pieces of clothing were mutilated, the bodies were in shallow holes, and they had no shoes. Ramos shudders before he spits it out: “My conclusion is that it seems like there wasn’t really anything to be concerned about; [the people who committed the murder] were relaxed as they acted.

Fred reflects about the possibilities that a good, systematized registry could mean for the work of those who are searching for disappeared persons amidst tens of thousands of unidentified bodies. “They’re looking for their children who have already been found by the authorities, but they’ve never been told.”

Well systematized, the causes of death could be a filter to help reduce the universe of disappeared persons and give their families certainty. “They show us clothing and complete bodies of indigent people or people with no family. But the bodies we want to see, the ones that are injured, in graves or on the streets, those are the ones they don’t want to show us,” complains Garay. So, she says, they have no choice but to “stand at the foot of the grave.”

The clothing Ramos photographed have no flesh or faces. Despite everything, they tell the story of their lives through the little details of their death.

“We need to bring them home,” says Victoria Garay. “We need to give them back their identity.”

The absence is erased by bringing their names back.

This photo-essay was developed thanks to support from journalists Lucy Sosa and Raúl Fernando Pérez in Chihuahua.

Translation: Heather Dashner, CISAN/UNAM.

This piece is part of “Fragments of the Disappearance” a special project published by Quinto Elemento Lab. You can read this article in Spanish here.

Súmate a la comunidad de Quinto Elemento Lab

Suscríbete a nuestro newsletter

El Quinto Elemento, Laboratorio de Investigación e Innovación Periodística A.C. es una organización sin fines de lucro.

Dirección postal

Medellín 33

Colonia Roma Norte

CDMX, C.P. 06700