A nation overwhelmed by its dead

Since the beginning of the “war on drugs,” more than 38,500 unidentified bodies have been delivered to the country’s morgues, ending up in refrigerated rooms, mass graves, or medical schools. Some of these bodies were disappeared from the state government registries, left in funeral homes or incinerated. This investigation reveals the magnitude of the country’s crisis in dealing with the remains of murder victims.

By Efraín Tzuc and Marcela Turati / Quinto Elemento Lab

September 22, 2020

In March 2008, the Diario de Juárez headline read: “The bodies of the murdered clog the morgue.” That month forty non-identified bodies were sent to mass graves. By May another headline sounded the alarm: “The morgue is full.” The morgue was equipped with two metal oprtating tables, fourteen bodies waiting for an autopsy, and ten more bodies that no one had come to claim. In July, the headline again read: “They fill up the morgue again.” By then, an average of eight bodies arrived daily, and another fifty were excavated from a clandestine grave. By December, when the autopsy room had been remodeled and expanded, another bit of bad news turned into a prediction: “The morgue collapses with too many dead.”

News stories about the imminent collapse of the Forensic Medicine Services (Semefo, in Spanish) in Ciudad Juárez would be repeated across the country, over and over again, over the following fourteen years: whether due to lack of space and staff, refrigetartor malfuntions, the admission of the cadavers of migrants whom no one comes to claim, or the long wait for labratory analysis. The government only formally acknowledged the problem last year, calling it a “forensic crisis.”

No government authority has clarified the magnitud of the crisis.

Between 2006 and 2019, thousands of cadavers were admitted to the Forensic Medical Services across the country. Quinto Elemento Lab obtained data revealing that, by 2019, 38,891 bodies remained to be identified.

In 2006, there were only 178 unidentified bodies in the forensic system. By the following year the number doubled to 433. The phenomenon became ever more massive: there were 4,408 in 2018, and in 2019, the first year of Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s government, another 4,905 unidentified bodies had accumulated.

Calderón legacy in this ordeal was of 9,349 unidentified cadavers. Peña Nieto’s was of 17,590.

Over that period of fourteen years, the number of unidentified bodies admitted into morgues increased by a thousand percent.

Unidentified bodies in Mexico. Graphics: Omar Bobadilla

Those nearly 39,000 bodies are part of the cost of fourteen years of a politics of militarization begun during the administration of Felipe Calderón, whose “war against drug traffickers” created a blood bath and threw gasoline onto the criminal organizations’ on-going territorial disputes. During that same time, 289,000 people have been murdered and more than 70,000 have been disappeared.

The paradox is that everyday, across the country, families organize themselves to go out searching for their disappeared relatives, often with picks and shovels and digging with their own hands. Every year mothers of migrants cross Mexico looking for clues as to the whereabouts of their sons and daughters that never went back home. Amongst those 39,000 bodies under the State’s jurisdiction could lie the answer these families lack. The State has those bodies, but it does not always have the political will to send them home, where they may have a proper burial.

What is known about those bodies?

This investigation is based on documents acquired through public information requests to all 32 states and the Mexican federal attorney general. The investigation shows that 25,833 unidentified bodies are male, 2,419 are female, and 10,639 did not specify sex in the documents.

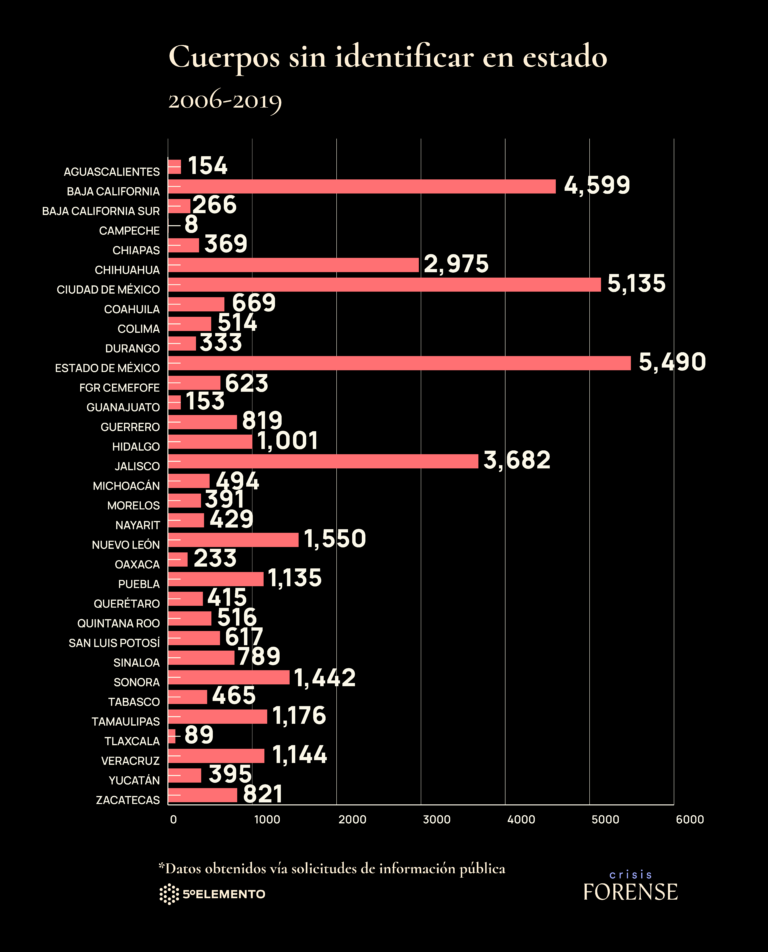

Five states concentrate half of the bodies: Mexico City, Baja California, Jalisco, Mexico State, Chihuahua and Nuevo León. They together registered 21,881 unidentified dead bodies.

Unidentified bodies by state.

To date, no government office, no report or analysis has clarified how many of these anonymous bodies there are nor where they are located.

Thousands of bodies arrived at morgues that lack national guidelines for the processing, indentificaiton and storage of bodies, morgues with insufficient staff to face the wave of violence. This situaiton put the furture identification and traceability of the bodies at risk.

Every so often news stories apprear describing the improvised experiments in some states to try and keep the unidentified bodies from getting parked on their metalic tables, and to thus create space for the new arrivals. The most famous cases involve the experiments that violated all the rights of the deceased.

The Morelos government, for example, dug its own clandestine mass graves in Tetelcingo between 2010 and 2013 in order to hide 117 bodies. The Morelos government buried another 84 bodies without any kind of register in the Jojutla cemetary. Those illegal burials were discovered by families of the disappeared who, outraged, pressured for the bodies to be exhumed in 2016 and 2017.

In September 2018, an abandonned trailed filled with hundreds of bodies was found in Jalisco. What looked like a narco plot, turned out to be the work of government authorities who piled up 322 bodies in rented trailers, one of which, without refrigeration, was driven through the streets of Guadalajara.

Mobil morgues were not an innovative solution: there have been previous experiments with them in Acapulco, Chilpancingo, Xalapa, Tijuana and Tamaulipas, where they are still in use. Before the international scandal which earned the name “the trailers of death”, Jalisco had given the order to incinerate 1,559 people in ovens: only 553 bags of ash contained the complete forensic records necessary to identify a body.

In addition to the constant overflow in Ciudad Juárez, morgues in cities like Acapulco, Chilpancingo, Cancún, Guadalajara, Xalapa, Torreón, Coatzalcoalcos and Tijuana have collapsed, as the forensic authorities in those states recognized, and as has been reported in the press.

In 2017, for example, the morgue in Chilpancingo went on strike: the workers protested against the fetid odors that emanated from the accumulated cadavers. In 2019, the morgue in Tijuana ran our of space and began to send bodies to the offices of the State System for Integral Family Development (DIF).

Where are the unidentified bodies?

Faced with their inability to store the bodies, morgues across the country found solutions underground.

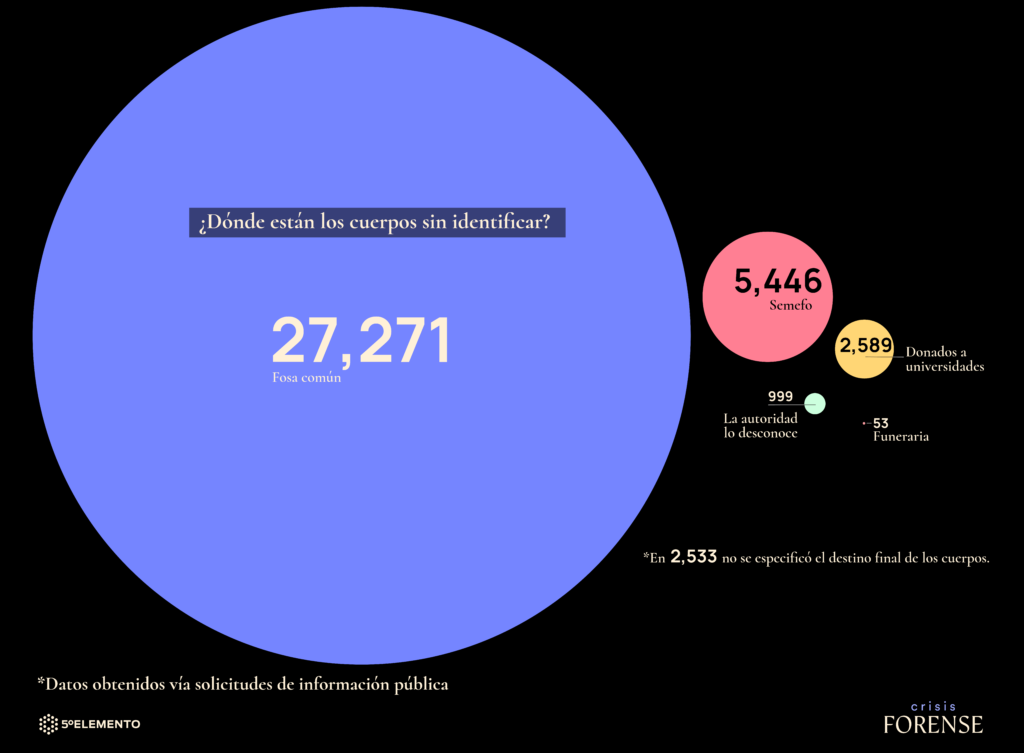

The forensic crisis turned the Mexican state into a burial machine: 27,271 unidentified bodies—70 percent of the total—went from the morgue to mass graves.

Miguel Alemán Forensic Cemetary in Tamaulipas. Photo: Mónica González

For many years, forensic workers put cadavers into plastic bags and sent them to mass graves without following any protocol that would allow for later identification of the deceased person. Burial locations and records were left to the municipal cemetary workers who dealt with them at their whim, often not following any order or digging individual graves.

In Coahuila, for example, during the implementation of the State Exhumation and Forensic Identificartion Plan, in 2017, officials found that the cadavers in the mass graves were not those indicated in the records, neither in number nor in description. In the irregular graves in Tetelcingo, Morelos, the state attorney general’s office buried 46 bodies and extremities that either did not have identifying information, or had illegible labels. Federal attorney general investigators went to retrieve 30 bodies and undug more than 100.

Such erratic procedures lead to what gets called “administrative losses.”

Hugo Soto Escutia, the International Committee of the Red Cross advisor in Mexico explains these losses as follows: “If identified, this person will go to a mass grave where there are more than 50 people, or 32 or 40 or x number. And no one knows which position the body was left in, on which level, etcetera. And there the State loses them. That’s why they are called administrative losses, due to an administrative issue of the State.”

The other most common destination for the unidentified bodies is into the drawers of the morgue. Fourteen percent of the unnamed bodies that do not end up in mass graves wait to be identified in rooms of drawers for skeletal remains, refrigerated chambers, or tables in the autopsy rooms. In such limbo there are now 5,446 bodies.

Drawers at the morgue in Nayarit Photo: Karina Cancino

But being closer at hand does not gaurantee being identified.

In 2011, for example, it was discovered that the modern instalations at the morgue in Ciudad Juárez “held” the bodies of 26 women. A group of mothers had been searching for soe of those women for years and had requested information at that very morgue. The State Human Rights Commission found that 47 bodies that were sent wandering about in the itinerant morgues in Jalisco had sufficient information to lead to their identification.

Among this portion of unidentified bodies stored in the morgues are those bodies extracted from the mass graves in Iguala and surrounding areas during the searches for the 43 Ayotzinapa students disappeared in 2014. Some 90 of those bodies are stored in the drawers of the federal forensic agency of the federal attorney general in Mexico City.

According to the information received, of the almost 39,000 unidentified bodies, 954 were incinerated: three in Tamaulipas and the rest in Jalisco. The only hope for those who are searching for them is that the state forensic workers correctly filed their photographs and genetic analysis. The federal attorney general’s office did not mention in its response the incineration of 10 bodies ehumed from the mass graves in San Fernando, Tamaulipas on the last day of Felipe Calderón’s administration.

At least 2,589 bodies were donated to medical schools. It is possible that medical students are learning with the bodies of people whose families are searching for them.

Universities such as the University of Guadalajara (UdG) have contributed to this humanitarian crisis: the UDG incinerated 118 of the bodies donated to it by the state forensic services.

In another 53 cases, private funeral homes have the human remains in their possession. In Oaxaca, Quintana Roo, and Tamaulipas, state prosecuters delegated their responsability to store bodies to these private businesses.

Funeral home chapel in Sinaloa. Photo: Luis Brito

The double disappearance

And what is worse, in seven states they lost bodies.

Such is the fate of 999 cadavers that the forensic authorities cannot account for, even though their employees were the last people to examin those bodies inside the morgues. The following states acknowledged this borderline criminal disorder: Coahuila, Jalisco, Nuevo León, Oaxaca, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas, Tlaxcala and Zacatecas. The final records of these bodies were lost in the institutional laberynth.

The case of the Jalisco Forensic Science Institute (IJCF) is paradigmatic: it responded to our requests saying that it was “investigating” the whereabouts of 355 bodies that had been admitted into its buildings.

The forensic authorities in Guanajuato, Guerrero, Jalisco, Quintana Roo, Tampaulipas and Veracruz did not submit information regarding the final whereabouts of 2,528 unidentified bodies: 6.5 percent of the national total of unclaimed bodies. It is only possible to know that the bodies were registered and that theu continue to be considered unidentified.

The Guanajuato State Attorney General evaded responding to the question of how many unidentified bodies remained in its morgues. After repeated requests through public access to information channels, it only acknowledged that it had “153 complete basic archives” with descriptions of characteristics that allow for later identification.

After submitting a complaint to the Guanajuato Transparency Institute, the state attorney general’s office turned over information about 701 bodies buried in a mass grave. It said, however, that it did not know how many of those bodies had been subsequently identified and did not respond to our interview request.

It is thus impossible to truly know the exact magnitud of the forensic crisis.

In this investigation we only include complete bodies and skeletons. The morgues also recieve hundreds of thousands of human fragments and remains. In a number of states across the country, criminals have used acid and fire to destory bodies and make them unrecognizable.

Final whereabouts of the unidentified bodies.] Graphic: Alejandra Saavedra

The Unknown Study

In June 2019, during the first work report of the National Search System for Missing People, the subsecretary of Human Rights, Alejandro Encinas, informed that there were 37,000 bodies that had possibly not had autopsies, 263 autopsy rooms with a combined capacity to store 5,171 bodies that, by March 2019, stored 8,116 bodies: 2,945 bodies beyond capacity.

Encinas did not descirbe the methodology they used, the number of deceased people who remained unidentified, the characteristics of their bodies, the distribution of them across the states, nor where they were at present.

The National Citizen Council, part of the National Search System for Missing People, an independent, civilian government body that monitors compliance with the National Law on Disappearances, also did not know how Encinas arrived at his number. “We, like everyone else, saw the Power Point presentation in the meeting. We had our doubts precisely regarding the methodologies used to come up with that statistic (…). We still don’t really know what methodologies they used to come up with 26,000 first, and later 37,000,” explained Volga de Pina, member of the National Citizen Council.

Encinas mentioned that the “forensic emergency” is the result of a lack of infrastructure, staff, resources, forensic cemetaries, and approved protocols for conserving cadavers.

Quinto Elemento Lab sent multiple public information requests for a copy of the complete study. The National Search Commission (CNB) denied all these requests, claiming that only the Federal Attorney General (FGR) had a copy. The FGR argued that the study was not finished.

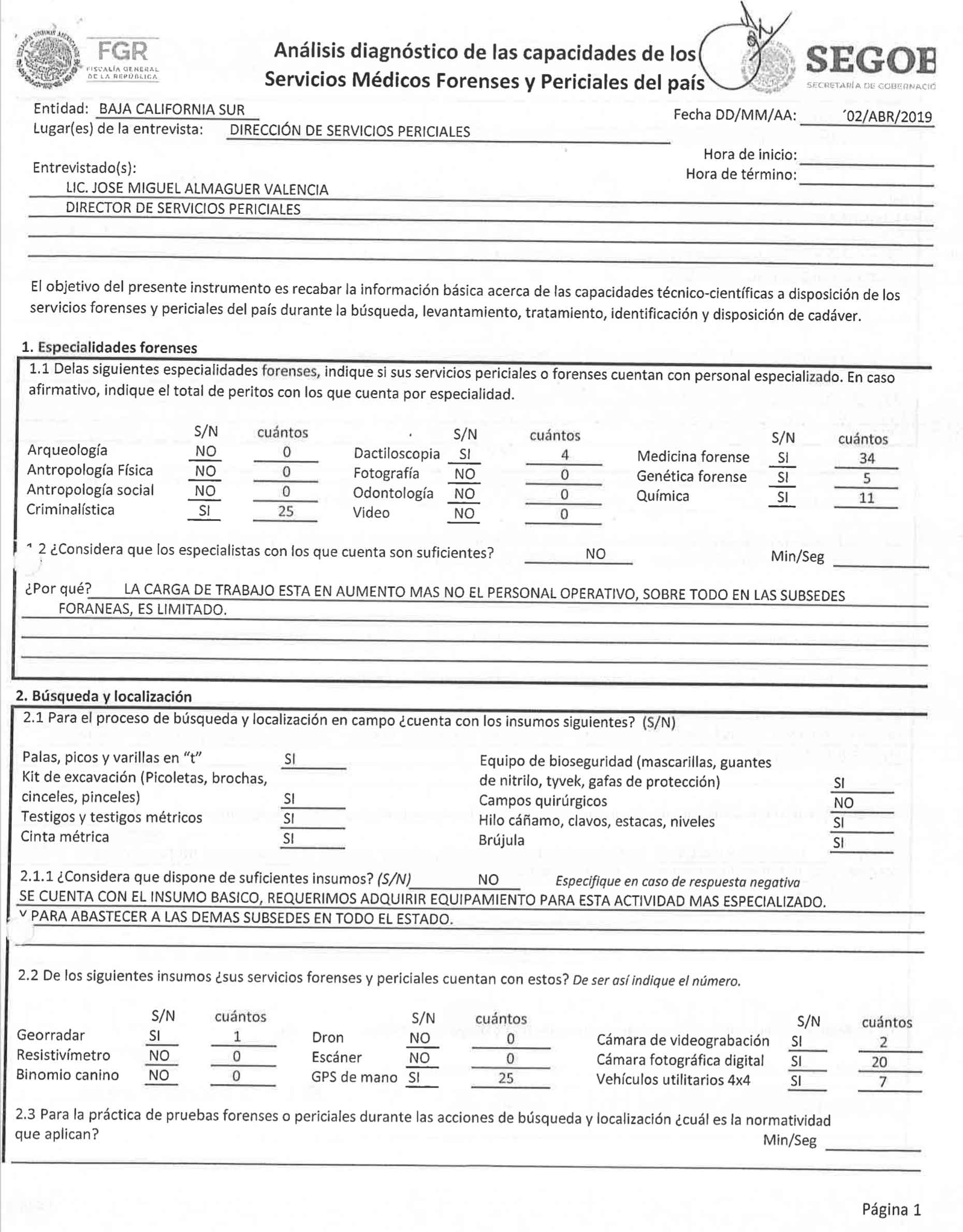

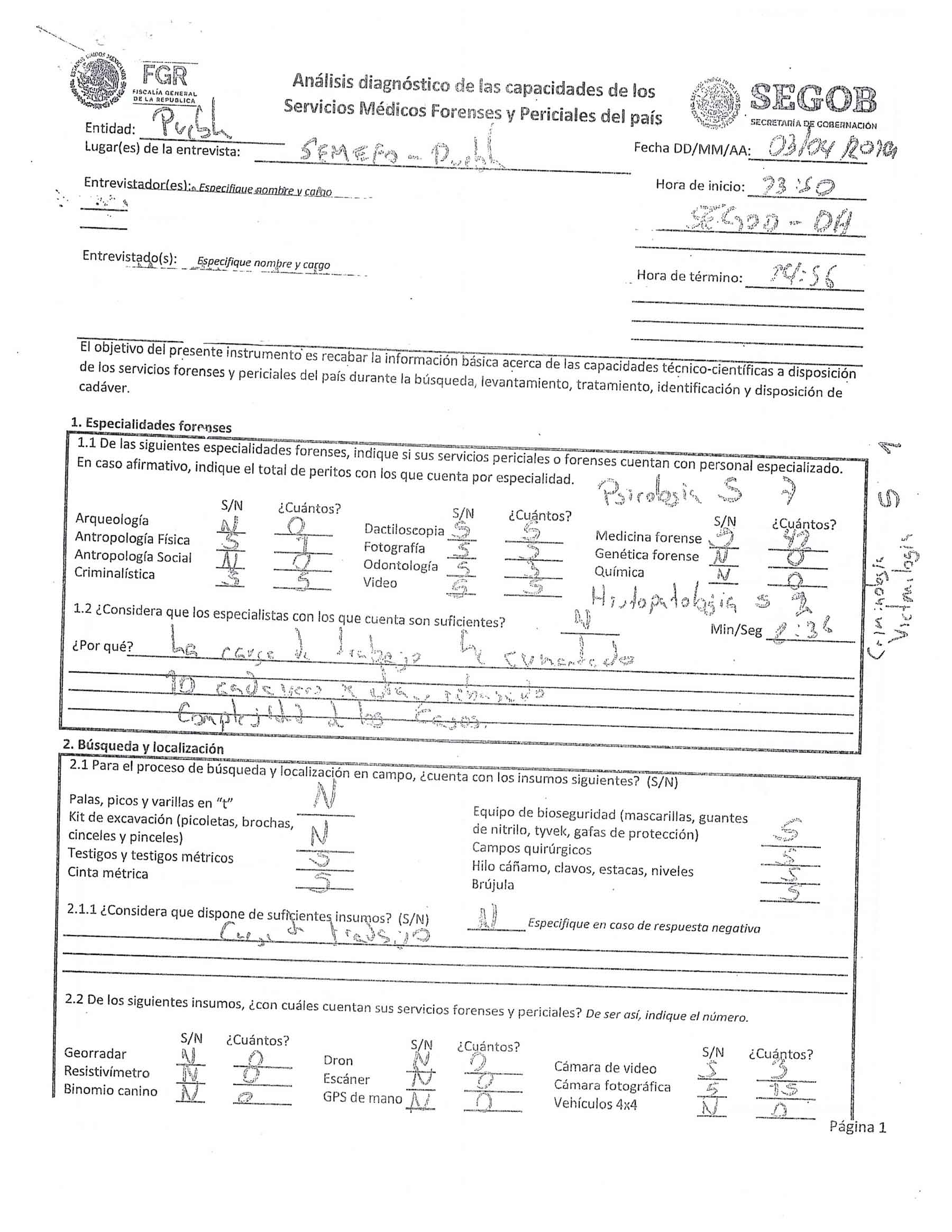

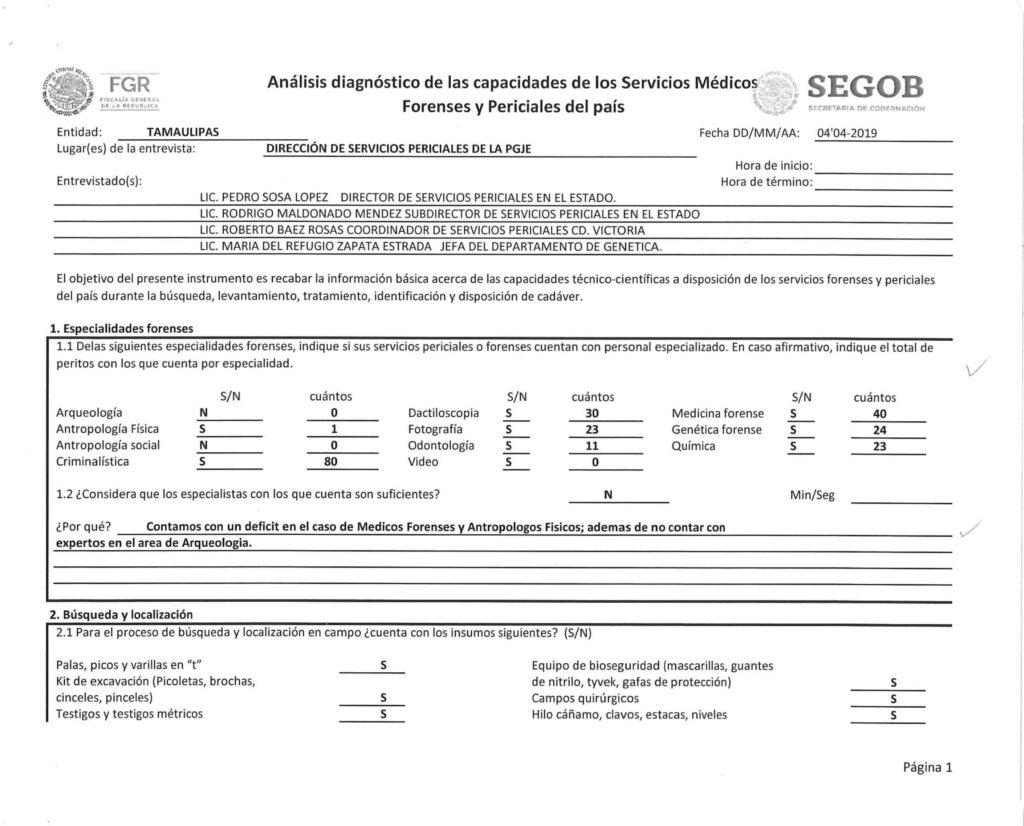

Baja California Sur, Puebla and Tamaulipas, in contrast, did send Quinto Elemento Lab a copy of the questionnaire they filled out for the federal study.

The answers that these three states sent for the federal forensic analysis reveal a devastating reality. In Baja California Sur’s case, the morgue services directors recognized that their workload was increasing without a corresponding increase in staff. The morgues in Tampaulipas, which receive about ten bodies a day, said they could take from three days up to a month, or in some cases two years if it does not have a genetic match, to identify a body. The questionnaire sent by the morgue services in Puebla is scant: written by hand, at times illegible and crossed out, one can read: “The workload has increased, 10 cadavers a day and overwhelmed. Complicated cases.”

Questionnaire answered by forensic authorities in Baja California Sur, Puebla, and Tamaulipas. Credit: Documents obtained via public information requests.

Anselmo Apodaca, the former director of the Federal Attorney General’s Forensic Servcices Unit, thinks it unjust to stigmatize the forensic medicine services by speaking of a “forensic crisis”.

Apodaca says that repeating the fact that there were “four trailers with 400 bodies” in Jalisco, or that in Guerrero families were given ashes that turned out no to be human does not lead to anything constructive. “That is all old news,” he said in an interview.

“I think it is unjust “to speak of) the issue of a forensic crisis. No. Here we have a violence crisis, one of crime that has impacts on the forensic area, obviously. But to call it a forensic crisis seems to me to place all the forensic workers in a position of maximum responsability for all this, when we have been giving our maximum effort.”

For Anselmo Apodaca, the violence combined with a lack of infrastructure, investment in technology, and staff, whose capacities have been overwhelmed. He also admits that in some states there was no vision when budgeting for forensic medicine units.

The morgues were not prepared for what was to come. They were caught unaware by the massive arrival of homicide and massacre victims who had to be treated with deficient infrastructure: in Coahuila, Sinaloa, Sonora, and Tamaulipas, private funeral homes leant the authorities their buildings. In other cases, the morgues did not have sufficient personnel, as the authorities in Baja California Sur, Puebla and Tamaulipas all acknowledge. In other cases, there was no investment in forensic medicine services. This was the case in Veracruz, where 80 percent of the budget allotted to forensic medicine was spent on other expenses. The morgues have tradicionally been treated as infested, second-class institutions when considering the allotment of state funds.

“The violence was increasing and the state governments in many places were abandonning the budgets that could have strengthened the medical forensic services,” said Apodaca, also a Federal Police commissioner who specializes in criminology. “Have not been strengthened, they were overwhelmed (…). The morgues were surviving with the budgets assigned in each state.”

Apodaca thinks that all the bodies that were identified should be counted, that they are many and show the good work being done in many morgues.

The study results that the government tries to hide, are revealed however, when other institutions have been able to take a look at how the forensic services are operating.

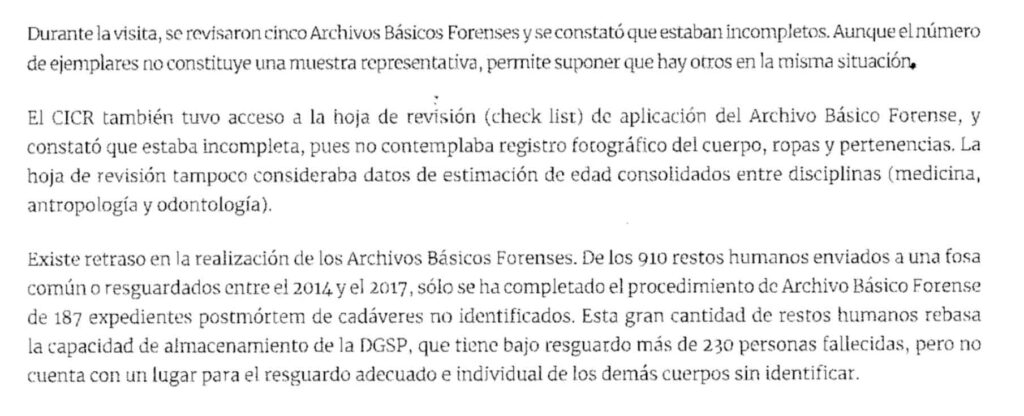

A study of the forensic capacity of the state of Veracruz carried out by the International Committe of the Red Cross—obtained by AVC Noticias—revealed that of the 910 bodies sent to mass graves between 2014 and 2017, only 187 had basic post-mortem documentation. The study also found that the documents pertaining to the bodies admitted to the morgue consistently lacked reporting on the precise location from which the body was recovered, whether the body has been identified or not, and the body’s present condition.

Red Cross study. Credit: AVC Noticias/Connectas

The Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF), an independent organization that collaborates with governments and family groups to identify people, and that participated in the Forensic Commission to review, together with the PGR, the unidentified bodies extracted from the clandestine graves in San Fernando, Tamaulipas, in 2011, found that state and federal authorities made a series of errors, as documented by the CNDH in its recommendation 23 VG/2019.

For example: 31 of the 60 exhumed bodies ended up in mass graves even though they could have been identified. They erratically cremated an unspecified number of bodies. They delayed the matching of genetic samples from relatives for more than four years. They mixed up the sketetal remains of different people. They lost belongings that accompanied the remains. They made reports on disappearances without important data. They handed over the body of a Mexican to a Guatemalan family and waited a year to remedy it.

In January 2020, the Jalisco State Human Rights Commission made a recommendation to the IJCF and the state Attorney General's Office in which it indicated that the data on the labels of 25 percent of the unidentified bodies had been erased. When the system produced a match between bodies and disappearance files from other states, no collaboration was requested to locate the next of kin. They also documented the late fingerprinting of bodies, the lack of confrontation of the DNA samples of people who were looking for a relative with the DNA samples of the bodies in their custody, and the lack of data on at least 700 bodies cremated in previous years.

The collapse of the forensic services constitutes torture for the families.

Discovery of skeletal remains in a hidden grave. Photo: Germán Canseco / Proceso

The forensic collapse

Quinto Elemento Lab also obtained information via Transparency (the Mexican federal institute for public information access) for this investigation on the overcrowded morgues in the country. At the end of 2019, 44 of 177 Semefo were overwhelmed. These are morgues in 18 states of the republic, as well as that of the FGR.

In other words, one out of every four morgues that stores bodies has surpassed its storage capacity. The Xalapa morgue kept 364 more bodies than can fit in its building. And the federal morgue services of the FGR had 164 more bodies. The North Zone of Quintana Roo suffered a critical situation: the storage area exceeded its capacity by 85 bodies.

The states of Oaxaca, Hidalgo and Veracruz acknowledged that they have resorted to using refrigerated containers for excess bodies, but in their responses they did not clarify the capacity of these makeshift morgues.

Ciudad Juárez’s morgue reported an excess of 45 bodies.

In 2018, the Juárez press reported that the morgue required new funding, that 420 corpses were admitted per month (half of them, homicide victims), that 231 corpses lacked the genetic profile analysis, that a person searched for his son for 8 years and found him in the morgue, and that victims protested to demand information on stored bodies.

Journalist Luz del Carmen Sosa is author of the first stories on the over-filling of the morgues in 2008. Over these past years she has witnessed the expansion of morgue facilities and equipment, new hires and courses for staff, laboratory certifications and, in contrast, the endless waiting lines for autopsies; the caravan of mothers of disappeared youth who asked to audit the morgue to search for their daughters; the failure of the refrigeration system due to excess bodies; the murder of the chief of expert services; the discovery of clandestine graves that made Chihuahua second in the nation; the bodies that remained for years without being identified although their families claimed them; the systematic burials of strangers in municipal cemetery graves to vacate space, and the repeated collapsing of the morgue.

Ten years after writing her first stories on the subject, in 2018, Sosa documented 584 unclaimed bodies at the morgue.

National Missing Persons Search System. Photo: Benjamín Flores / Proceso

In February 2019, Undersecretary Alejandro Encinas promised that five Regional Forensic Institutes (in Sonora, Coahuila, Nuevo León, Mexico City and Veracruz), 15 forensic cemeteries -temporary corpse storage facilities- would be created in nine states and “extraordinary” support would be provided for forensic services in overwhelmed states, to strengthen state capacities and for the CNB.

In December 2019, under pressure from the families of disappeared persons and also with their participation, the Extraordinary Forensic Identification Mechanism (MEIF) was created. The MEIF is a group of experts with technical and scientific autonomy that will support the identification of bodies or skeletal remains across the country. Despite the urgency of the families of disappeared persons to find their loved ones, the MEIF remains without a director and has not begun to operate.

Yolanda Morán, who is looking for her son Dan Jereemel Fernández and is a spokesperson for the National Movement for Our Disappeared in Mexico, thinks that the budget is insufficient. She is hopeful that the Mechanism will start on January 1.

To date, one promise has been fulfilled: last August Coahuila received a Regional Identification Center from the federal government. On September 17, in Michoacán, the first stone of what will be a Forensic Protection Center was laid.

The head of the ICRC delegation for Mexico, Jordi Raich, reported last year in an interview that it has been calculated that, in an ideal scenario, with the necessary specialists and resources, an estimated 2,000 bodies could be reviewed per year, to try to give them back their identities. This means that it would take 20 years without counting the new income. "If you don't enter a scene (of violence), it will worsen even more."

Mass grave at the Centenario cemmetary in Los Mochis, Sinaloa. Photo: Luis Brito

State Analyisis: “Classified Information”

In 2018, a dance of statistics began regarding the unidentified bodies in the country.

By April, the undersecretary of Human Rights in the time of Enrique Peña Nieto, Rafael Avante, released that there were 35,000 unidentified bodies in the country’s morgues. He never clarified his source or responded to requests for public information. At the end of his term, he gave another piece of information to Alejandro Encinas, who would succeed him in office: there were 26,000.

In January 2019, when leaving his post, the National Search Commissioner, Roberto Cabrera, affirmed that there could be 36,708 unidentified corpses, according to the fingerprint records in the Mexico Platform.

Before the end of Enrique Peña Nieto's six-year term, the then Attorney General's Office (PGR) -now FGR- carried out the “Diagnosis for the National Exhumations Program”, which was never presented to the public, but estimated at 16,520 the number of corpses preserved in morgues or buried in mass graves in 26 states.

The latest effort to clear up the mystery of post-mortem records of unidentified bodies was made in March 2019, after the National Search Commission, the Office of the Special Prosecutor for Human Rights of the FGR and the Undersecretary of Human Rights of the Ministry of the Interior (SEGOB) were urged by the President of the Republic to prepare a study.

Officials from the different agencies were sent from March 29 to 31 to each of the states to speak with the people in charge of the autopsy rooms and fill out a long questionnaire on facilities and capacities, the number of specialists and of bodies.

Halfway through the year, Encinas would present the results: there were 37,443 bodies that had probably not had an autopsy. He did not mention more.

In 14 years no official has presented more than statements. No one has submitted a full report.

The CNB and the FGR denied all requests through public information channels to access to their study documents.

Their analysis indicates that in the country there are 263 autopsy rooms with an installed capacity to store 5,171 bodies that -as of March 2019- had 8,116 bodies, which represented an overcrowding of 2,945 bodies. And that the cause of the "forensic emergency" was the lack of personnel, infrastructure, resources, specialized cemetaries and approved protocols.

The now independent consultant Anselmo Apodaca, who in 2019 was general coordinator of the FGR's Expert Services Unit, explained in an interview that the study was not made public to avoid a beating between political parties based on the performance of state forensic services.

“(It was) so as not to expose anyone, because it was also a political issue. The expert services do not handle the political issue, but some states were reluctant, due to their governor, their attorney general, to give the data properly. This was at the beginning. (Later) a consensus was made, we really sensitized all the experts' directors so that they, in turn, sensitized their attorney generals. It was not an easy job because everyone feels that they are the owner of their information, but when talking about databases you cannot be the owner of their information," he said.

He added that all the doubts were discussed with the morgue directors. Another source consulted on condition of anonymity mentioned that it was never possible to standardize the results: in the rush to give a quick response to the president, whoever was available was sent to audit the morgues and many did not understand the forensic jargon and, upon their return to Mexico City, failed to translate into technical details.

Either by consensus between authorities or because it was never finished, the truth is that the document is still under lock and key.

Quinto Elemento Lab’s series #ForensicCrisis and the Where to the Disappeared Go project reveal the collapse of forensic medicine services in Mexico and the consequences for the thousands of families searching for their loved ones and for the thousands of bodies that still remain to be identified. Follow it here: https://www.quintoelab.org/crisisforense/

Súmate a la comunidad de Quinto Elemento Lab

Suscríbete a nuestro newsletter

El Quinto Elemento, Laboratorio de Investigación e Innovación Periodística A.C. es una organización sin fines de lucro.

Dirección postal

Medellín 33

Colonia Roma Norte

CDMX, C.P. 06700