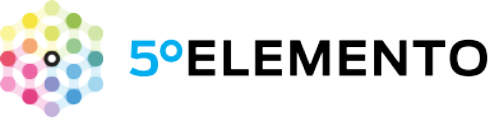

Honduras to Chiapas: A Human Trafficking Pipeline

Comalapa, in the Mexican state of Chiapas, is a disputed territory for organized crime, is a place where Honduran women are sexually exploited and give birth to children without nationality. This is the story of an illicit business that operates with impunity and also the story of victims who managed to escape from their captors.

By Rodrigo Soberanes / Quinto Elemento Lab

April 3, 2024

O

n a street in Frontera Comalapa, in Chiapas, on the Mexico-Guatemala border, is the birth house where Ana and Rosa, two sisters from Honduras, wait to see their friend Daniela, who has just had a baby.

“We want to leave,” says Rosa, overwhelmed. Ana agrees. They came to the birth house about four hours ago, and the heat and humidity are already weighing them down.

The time they are allowed to spend away from home is limited. They glance at the birth house entrance constantly, in a state of alertness. It’s a November day in 2021 and they are here to accompany Daniela, but they are running out of time, because their lives are not their own; they are controlled by someone else, a man they describe as powerful and violent.

Da clik aquí para leer este reportaje en español

Ana, who is 21 years old, calls him “my Mexican.” Rosa, who is four years older, tenses and takes a deep breath as she listens to Ana speak. Neither of them mentions the man’s name. He is a member of a criminal group, and he has a relationship with Ana: he is the father of her daughter.

The birth center receives women from around the region, from neighboring Guatemala, and, for the past 15 years, victims of human trafficking from Honduras. It’s a simple cinder block building, with a waiting area and a room for delivering babies. The toilet and sink are outside, surrounded by a lush garden larger than the footprint of the house.

The three young women are forced to work in bars and cantinas in Frontera Comalapa —the name of the municipality and its main town— where organized crime has built up a lucrative business trafficking Honduran women for purposes of sexual exploitation.

The term “human trafficking,” according to the Palermo Protocol adopted by the United Nations in 2000, refers to the “recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power, or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation.” It can include sexual exploitation, forced labor or services, slavery, servitude, or the removal of organs.

On September 23, 2023, Frontera Comalapa made headlines when gunmen identified as members of the Sinaloa Cartel paraded in armored vehicles through a crowd of people who celebrated the group’s victory over the rival Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG). Both organizations are fighting for control over drug, arms and migrant trafficking operations along the border.

The Sinaloa Cartel has a presence in the area dating back to the late 1980s. But in 2018, an election year, violence between criminal groups intensified, according to a report by Avispa Midia. The incursion of the CJNG coincided with the arrival of Morena, the party of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

For the purposes of this report, we interviewed victims of trafficking in Frontera Comalapa, witnesses to these crimes, members of organizations that document them, and midwives who work in the area — a total of sixteen sources, most of whom, for reasons of security, are identified using pseudonyms. We also traveled migration routes between 2017 and 2022, and made visits to Frontera Comalapa, Chiapas between 2019 and 2022.

‘With or against us’

For years, Josefina supported female victims of human trafficking in Frontera Comalapa. Until 2018, when Honduran women began arriving at the shelter “suddenly, like they were on the run.” The women were being forced out of the cuarterías —the apartments, small hotels, and other dwellings built from thin air in which they lived— because the criminal landscape had shifted. The fight between the Sinaloa Cartel and the CJNG had begun.

In 2022, Josefina decided to leave; she knew that an upsurge in the violence between disputing cartels was imminent.

The eruption of fighting in May 2023 displaced more than 3,000 people, who fled their communities to escape the bloodshed. The residents of Frontera Comalapa had two options, according to published first-hand testimonies: leave, or obey the orders of the CJNG, issued through Maíz, an acronym for the Mano Izquierda group, which is considered the social base of the cartel.

Two years earlier, in August 2021, the main access roads into Frontera Comalapa —from San Gregorio Chamic to the north and Motozintla to the south— were closed by members of the Jalisco cartel. “The narco groups had taken control and seized all the local organizations — civilian and campesino, commercial, and others. They dug in their heels and said, ‘Okay, everyone, you’re either with us or against us. Which is it gonna be?” one local resident explained at the time.

Many organizations disbanded and were integrated into Maíz. Public transport vans and businesses display the group’s logo. If an incident occurs, the criminal organization tells its members to block the highways, to not allow anyone through.

The violence has not stopped. In early January, 2024, there were more confrontations, power outages, and road blockades in different communities across Frontera Comalapa and in nearby municipalities like Chicomuselo and Motozintla. The Mexican newspaper Reforma reported that, according to local residents, neither the Army nor the National Guard had been able to enter the conflict zones.

Frontera Comalapa is a region shrouded in silence. It took several years to unveil the details of how trafficking networks operate there. At every stage in the process, I had to follow security recommendations, circumvent evasive answers, engage with sources who agreed to talk but later regretted it, accept conditions of anonymity, and heed warnings.

It is these stories —of Josefina, who spent years protecting victims in secret, and of the nun Lidia Mara Silva de Souza, who bore witness to the violence of traffickers in Honduras; of women like Ana, Rosa, and Cony, who attempt to escape or resign themselves to the fate that brought them to Frontera Comalapa, and of the midwives who support and care for these women, so that they can birth strong, healthy babies— that allow us to map the route of the trafficking underworld, from its starting point to its end, at times even a luminous one, when the women succeed in leaving behind their captors.

According to the United Nations, the illicit business of human trafficking generates up to $36 billion USD in global profits every year.

Migrants in Limbo

Rosa and Ana first came to Frontera Comalapa in 2018. Three years later, they’re still here, living in a cuartería and working at a cantina in the center of town. It’s a prison without bars. Their every move is surveilled by the criminal organization that paid to bring them here, which in this municipality is controlled, they say, by “the Mexican.”

“My Mexican abuses me. He knows everything I do, that’s why I don’t go out anymore,” Ana tells me at the birth house, which smells freshly cleaned and has a dirt patio dappled with pebbles from a river that runs nearby, so close that it can be heard from the house.

Before its founding in 1928, Frontera Comalapa was called Cushu, which means “grilled corn” in Mam, a Mayan language. Other accounts collected by anthropologist Enriqueta Lerma Rodríguez claim that the name Cushu derives from cusha, a traditional maize moonshine produced in the region for centuries. In her book Los otros creyentes, anthropologist Lerma Rodríguez includes a testimony that attributes the name Frontera Comalapa to attempts to delineate territorial boundaries with Guatemala.

It was in the second half of the 1990s, according to researcher Nicanor Madueño Haon, that the “first migratory wave” of Honduran women arrived in Frontera Comalapa, which coincided with the increased militarization of the state following the uprising of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation in 1994. The growth in the number of cantinas staffed by foreign women during those years was related to “the phenomenon” of human trafficking in the region, he notes.

In 2012, the government of Chiapas reported that, during the previous five years, it had managed to dismantle 33 gangs involved in human trafficking. According to public records, between 2015 and September 2022, the state prosecutor’s office opened 36 case files on the crime. They did not provide specific information regarding the number of Honduran victims.

A 2021 report on human trafficking in Mexico, published by the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) using information provided by the state prosecutor’s office, found an increase in these numbers: between August 2017 and July 2021, 62 case files were opened for human trafficking investigations in Chiapas, and 40 criminal cases were initiated at the local level, with none at the federal level. The CNDH reported a total of 84 victims. All told, these cases resulted in five convictions and two acquittals, with eight people imprisoned for the crime in Chiapas.

At the national level, according to the report, there were 3,896 victims of trafficking identified during that same period, of which 2,934 (75 percent) were women. Ninety-three percent of the victims whose identities could be established were Mexican. Most of the foreign victims were Colombian (41), Honduran (40), and Venezuelan (38).

Two officials from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) who research human trafficking in Central America say that somewhere between fifteen and seventeen people, including several public officials, are involved in any given chain of human trafficking connecting Honduras to Frontera Comalapa, from the moment women are recruited to their ultimate captivity and sexual exploitation. “There’s the recruiter, the trafficker, the people who host victims during transit, the host [at the final destination], and the women who cook,” one of the officials explained in an interview.

The managers who run the business work with people who have access to the victims’ inner circle. Typically, their first contact is a family member or friend who convinces them to move to Frontera Comalapa with the promise of a well-paid job.

Between both ends of the chain are men and women who travel with them. At Guatemala’s immigration checkpoints, it is common to see traffickers, accompanied by their victims, hand over several passports at once to the officials behind the kiosk windows, without any agent asking questions or trying to stop them. Then there are the people hired to host the women in transit through Guatemala. And the managers of the hotels where no one speaks about what goes on inside, least of all to the authorities.

Once in Mexico, after crossing through official or unauthorized border routes, there are more public officials and authorities —migration agents, police, prosecutors— who see the women and do nothing. The victims are constantly under the thumb of criminals.

Thus, there is a constant flow of trafficking victims from Honduras — women who, when they find themselves pregnant, seek help at birth houses in Chiapas to have their babies, who are born without nationalities, because Mexico’s Civil Registry refuses to recognize birth certificates issued by midwives, according to testimonies from the midwives themselves.

For these certificates to be valid in the eyes of the state, midwives must be registered with a health sector institution; if they are not, the birth must be recorded by a health unit. In the latter case, midwives are limited to providing a record of delivery, which has no official value.

Ready to run

Rosa talks the least of all. She lulls herself in a rocking chair; she says she wants to leave, but she doesn’t have the will to. No desire for anything, years spent in sadness. She wears shorts and a cotton blouse. Today, she is taking a break from having to wear a dress and make-up.

Ana sits on the edge of a wooden armchair with her back straight and her hands on her knees, as if ready to spring up at any moment. She wears an orange strapless dress. She is visibly aware of the voices coming in from the street, and the sounds of the cars and motorcycles outside.

My meeting with the two Honduran sisters is an opportunity to learn about the business of trafficking. An intermediary, a friend of Rosa’s, set the date, time, and place for the interview. What she did not plan for was that her friend Daniela would give birth that day.

The cuartería where Rosa and Ana live is in the center of town, a few blocks from the main city park, in an area full of street vendors, taxis, and shuttle vans. In the adjacent rooms are more young women from Honduras, forced to work for the traffickers.

On any given day in hot and hectic Frontera Comalapa, women walk to the bars. Their phenotype gives them away; they try to go unnoticed, but they stand out from the women local to the region. They tend to be taller, and they have Caribbean accents.

“We get called ‘Honduran whores’ all the time on the street. ‘Estas catrachas son putas,’ stuff like that,” Rosa says.

Some of the women walk from the cuartería to a nearby bar where they work as ficheras —waitresses who entertain customers and get paid by commission: the more booze they get clients to drink, the higher their pay. Others take cabs to travel to cantinas in nearby rural communities.

Sometimes the girls don’t come home, either because they run away, disappear, or are killed, their bodies left abandoned. Many wind up in the mass grave at the municipal cemetery, according to Josefina, the woman who shelters trafficking victims. “They kill women here all the time and bury them wherever,” Rosa says.

As the sun sets, the heat lifts a little. Ana speaks of her rage, of her refusal to go on living in bondage to her “partner,” the man in charge of the criminal group —she wouldn’t say which one— that brought her to this place. She no longer wants to live like this, without her freedom. “They say there’s work in Tijuana. I have contacts in the United States,” she repeats, as if it were a mantra.

Her mind is made up: she plans to flee for Tijuana tomorrow; she has already bought tickets for her and her two children.

Escaping Frontera Comalapa is not so easy.

Las jefas

One spring night in 2021, two men and a woman, all Hondurans, took a bus heading south, tasked with bringing young women back from their country to work in bars in Frontera Comalapa.

In the same bus that departed La Mesilla —a Guatemalan border town less than 20 kilometers from the Chiapan municipality— sitting behind the group of traffickers was a field worker with the Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS), the first international humanitarian organization established in Frontera Comalapa to attend to the migrant population forced to stay in the area.

On public transportation in the region, it’s common to hear radio advertisements for evangelical pastors and healers selling “miracles,” coyotes offering to take people to the United States, and money lenders offering to pay for the trip. Radio stations advertise endless promises related to migration... and to human trafficking.

That day, on the bus, the criminals were exchanging audio messages to their contact in Honduras, and were playing the responses over speakerphone. Their interlocutor —the first link in the trafficking chain— was most likely a family member or friend, someone close to the girls they planned to pick up the next day.

“They were telling them where they’d be waiting for them, because the bus’s final destination was Honduras, so it would turn around and head back right after arriving. Then they told them not to worry, that [the girls] were ready,” the witness from JRS said.

The traffickers responded that the girls —they didn’t specify how many— would “return safely.” When they were done exchanging messages, they started talking to each other. “They said that a woman who owned a bar, una jefa, had promised them money for the women.”

There are many jefas in Frontera Comalapa. They are key to the business, because they are responsible for receiving the young women when they arrive, hosting them for their first few days, and telling them, when the time comes, that they’ve fallen into a trap. This cold shower of reality is released in a trickle, because it’s the jefas’ job to make sure the victims don’t run away. They are masters of subtle threats and blackmail; they are the ones who do the girls up and hand them over to the bar owners, though sometimes the jefas are also, themselves, the owners.

The witness account of the conversation between criminals continues: “They were talking about how well they were being paid. They were happy and in a good mood. We were traveling at night. Someone told them ‘shhh!’ because they were talking so loud.”

Police stopped the bus several times on its way through Guatemala. Officers boarded the bus, recognized the traffickers, and made them pay a bribe to continue on their way. It wasn’t a problem; the traffickers were expecting it. “They already knew the situation, and had enough money to pay,” said the source, who has been traveling these routes for five years.

When they got to Guatemala City, the traffickers took another bus to Honduras. The witness lost track of them, and doesn’t know what became of the girls they went to look for.

The Promise

In Victoria, a municipality in the department of Yoro, in northern Honduras, a young man named José was friends with Ana and Rosa. They all lived on the same block. He was someone “we had already known for a while.” In 2018, he told the two sisters about a lovely place in Mexico, where there were “good jobs working in restaurants.”

For Ana and Rosa, a secure job was an irresistible proposition. So José convinced them to go, and took them with him. It was a two-day trip. They left Victoria for the Gran Central Metropolitana station in San Pedro Sula and got on a bus heading north.

They passed by Ocotepeque, a coffee-growing town that often serves as a rest stop for traffickers and smugglers. After crossing the border near Agua Caliente, a mountain town that marks the eastern end of Honduras, they headed to Esquipulas, in Guatemala, where they did not stop to visit the venerated Cristo Negro — a ritual performed by millions of Central American migrants.

In the line that forms outside the basilica that enshrines the Black Christ, single adults are joined by unaccompanied children, families and groups of people taken there by coyotes, to pray before the 16th century image before beginning the most difficult part of their journey.

The women continued past Esquipulas and arrived in Guatemala City. Ana and Rosa talk about the hotels near Zone 1. The authorities there don’t come around asking questions; they are hotels, and at the same time, safe houses.

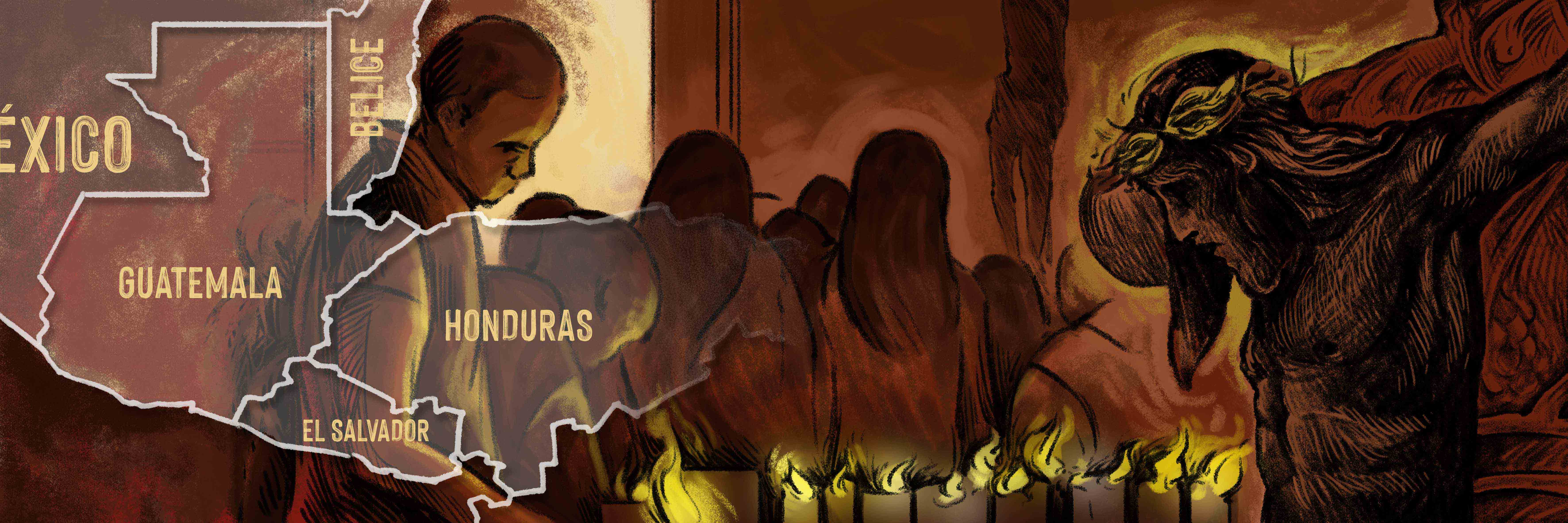

It was at that point that the women were stripped of their passports and IDs. Their trafficker asked for the documents, supposedly to conduct some bureaucratic formality, then never returned them. During their first night in Guatemala City, staying in the small, dirty, and uncomfortable hotel, the sisters sensed that something was wrong. But they were already trapped. They were out of their country with no documents. They were on a moving train and couldn’t jump off.

From Guatemala City, they traveled another 300 kilometers to the border crossing that separates La Mesilla, in Guatemala, from Ciudad Cuauhtémoc, in Mexico. The border town is crawling with backpackers; they come from San Cristóbal de las Casas, in Chiapas, to travel to tourist magnets in Guatemala, like Lake Atitlán or Antigua.

In La Mesilla, stores and businesses built of rusted metal line the streets, on the verge of collapse; people offer to exchange quetzales for pesos, and vice versa. Sellers peddle bulk foods like beans, rice, and milk, or cleaning and hygiene products, in a sprawling informal market.

The tourists are easy to recognize; they observe, as if on safari, an alien precariousness.

Without a Trace

Trafficking victims on their way to Frontera Comalapa, on the other hand, are not so easy to tell apart from the crowd. They are ferried along by sly and elusive criminals.

There is a small grocery store in La Mesilla where people enter to never come out. They walk past the cashier, make their way through the aisles, exit out the back, and emerge on a dirt road that leads to the Pan-American Highway on the Mexican side of the border. This, at least, is how one of the victims describes it. The potato chips and soft drinks are just part of the façade.

Rosa and Ana crossed the border and arrived in Ciudad Cuauhtémoc, with nothing but the clothes on their backs. “Sin nada.” José, their friend from their neighborhood back home, left them in the hands of a woman they didn’t know — una jefa. They will always remember him as the traitor who lured them into the net of “the Mexican.”

“I never imagined I would be coming here to do that kind of work,” Ana says.

The two sisters entered Mexican territory without passing through immigration inspection, without leaving any administrative record. As if they did not exist. Agents with Mexico’s National Migration Institute (INM), along with prosecutors and police officers, would only get to know them later, when they “grabbed their asses” as customers at the bar where the girls worked.

La jefa took them north. They traveled by car along the Pan-American Highway, as if heading to San Cristóbal, Laguna de Montebello National Park, or the Lagos de Colón as vacationers. But no: after a few kilometers, they turned left in the town of Paso Hondo. Then, they were swallowed by Mexico.

They headed west toward Frontera Comalapa, with Guatemala to their east, beyond a mountain chain that rises up like a line of giant pyramids engulfed in vegetation.

Had they kept driving north from Ciudad Cuauhtémoc, in another 20 kilometers they would have arrived in the town of San Gregorio Chamic, a community with less than 200 inhabitants, still within the borders of the municipality. There are only a few houses there, each separated from the next by significant distances. Some are birth houses. Some are bars. One of them was Josefina’s shelter.

In the town of Chamic, as it’s known for short, and in the surrounding rancherías, Honduran women live confined to small rooms, their lives mortgaged, working in miserable establishments where they are forced to serve as sex objects for the criminals who fight over control of the “the plaza,” according to the testimonies of Josefina and other local residents.

Before parades of narcotraffickers made Frontera Comalapa famous around the country and the world, there were already times when the violence would force public transportation along the highway cutting through the community to shut down every day from five in the afternoon onward.

The municipality of Frontera Comalapa, a hub of commercial activity, with 222 communities distributed over an area of 717 square kilometers, is mostly rural. The main town, which has around 20,000 inhabitants and takes less than ten minutes to drive through, is small; from there, it’s a winding, three-and-a-half-hour trip through mountainous terrain to Tapachula, the region’s main border city.

“[Frontera Comalapa] is like a regional cornerstone. It’s the main border crossing for a lot of municipalities, and there are a lot of unofficial crossing routes; it’s a super permeable border,” says Sergio Torres, a teacher from the area.

The strength of the quetzal —1 quetzal is equivalent to 2.15 Mexican pesos, or 0.13 US dollars, in March 2024 exchange rates— means that Guatemalans from La Mesilla and the surrounding towns travel to Frontera Comalapa to go shopping. “For example, during Christmas, people from Guatemala come and empty out the Coppel, the Aurrerá, and all those big stores. That’s why Comalapa has been growing so much,” Torres says.

After passing through Chamic, Rosa and Ana arrived in Frontera Comalapa. They prefer not to talk about their first few months there. Rosa focuses on the present; she talks about the heat, and about how she needs to leave, but is still reluctant to.

‘The body was a bar girl’

Ofelia is a midwife. She lives in a ranchería in Chamic, where she cares for both Mexican and Guatemalan women. Her main patients, however, are Hondurans who “show up when the pain gets bad,” in their final weeks of pregnancy, accompanied by their boss at the bar.

Ofelia is young and very busy. She travels around to the rancherías in this area of Frontera Comalapa; she massages wombs, she positions babies for delivery, she listens to their hearts with a stethoscope, she receives them at birth.

“Right now there are three [Honduran women] in the house,” Ofelia tells me in December 2021. “I don’t know if they’ll be relieved [give birth], because the señora [the boss] is coming to take them away.”

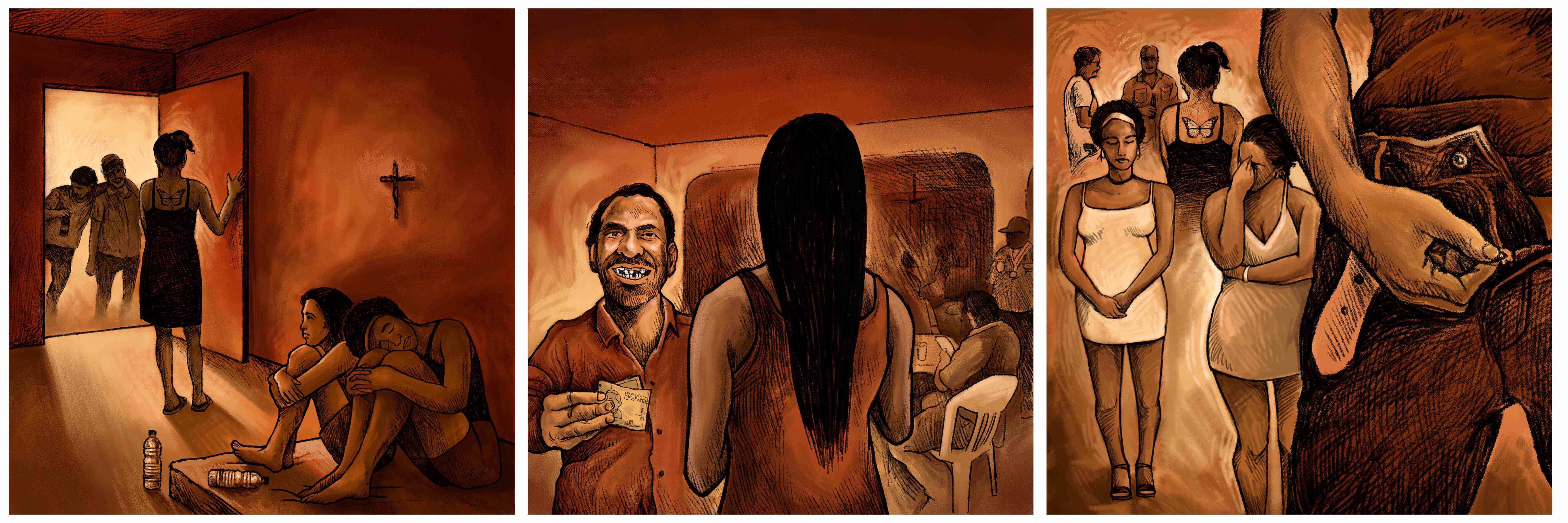

Often, because she doesn’t know the women’s names, Ofelia simply registers their births by stamping the baby’s footprint on a piece of paper in a notebook.

In Chamic, Josefina says that victims of trafficking first started showing up at her store in 2005, asking for food. The food, no matter how simple, filled their stomachs and opened their hearts. Bowls of soup turned into conversations, and then confessions.

They told her how they were forced to do “deviant things” at the bars, and at parties with the “powerful people” who controlled the business, Josefina tells me one hot morning in 2022, as we sit together at an unpainted wooden table in an open field, under a mango tree.

“People are very religious in Honduras, just like here. Most of the women were raised as Christians. When someone’s lived their whole life with all that fear and guilt, that’s the easiest way to control them. Often, once they start living that life, they don’t want to go home anymore. They lose their sense of dignity. It’s horrible.”

For years, women have poured out their souls to Josefina, who offers them massages, kindness, and care. She manages to help them without anyone knowing; she has the ability to go unnoticed in the region, to be a nobody. If she were ever discovered, she would never betray their trust.

A few yards from the table where we sit are the small rooms where she performs her healing arts. She helped build this shelter herself — a refuge where children have been born and women fleeing Frontera Comalapa have slept.

“In the beginning there were a lot of abortions,” she says. “They forced them to have abortions, sometimes using unsafe methods. That type of work is really dangerous, and the owners [las jefas] would give them lots of pills. They would show up here in terrible pain.”

And Josefina would take care of them. Her only limit was when patients were unable to expel the placenta. If that happened, they had to emerge from hiding and seek admission at a regional hospital.

Josefina says that, in the bars, women often get into conflicts with each other; there are some who “do everything,” and others who resist. “If you judge them, you don’t understand. These practices [abortion] alienate them from themselves to the point that they forget who they are. In the spaces we’ve provided them, they can recover. We give them antibiotics, medical check-ups, emotional support. After an abortion, a woman is never the same again. Everything changes.”

Often, the drug peddlers double as the owners of the bars where the women work, she says. “Sometimes these guys will fall in love and it’s terrible. They’re controlling and they abuse their economic power; they say, ‘I don’t want you to work here anymore,’ and [the women] say ‘okay.’ They’re always dreaming about someone coming to rescue them, about having their own home. So the men take them, but they don’t trust them.”

It’s a lawless border zone, Josefina says, where people have grown accustomed to finding dead bodies. “Bodies of women turn up in [the community of El] Pacayal, [in the neighboring municipality of Amatenango de la Frontera]; they kill them [there] and their bodies show up here, and vice versa.”

The insecurity crisis intensified in the region in July 2021, when the CJNG claimed responsibility for murdering the head of the Sinaloa Cartel’s operations in Chiapas, Gilberto Rivera Maravilla, alias “El Junior,” who was shot to death in the state capital of Tuxtla Gutiérrez.

“Frontera Comalapa became a strategic center for the cartels,” says Sergio Torres, the local teacher. The border smuggling routes are their main source of profits, he says. But the fight between criminal groups over control of the illicit market has also found its way into the bars, Josefina adds.

“They’re hunting the owners,” she says. “They take them away, and they don’t come back. These businesses are big money, too, because the women represent a double value for the criminals: the owners make money prostituting them, and they also force them to satisfy their sexual whims.”

The State Attorney General’s Office (FGE) reported sixteen total cases of intentional homicide and femicide targeting Honduran women in Chiapas between 2009 and 2022. These crimes were investigated in ten municipalities, excluding Frontera Comalapa. Of these cases, nine were prosecuted and brought to trial, and only one resulted in a conviction. Mexico’s Attorney General’s Office states that it has no information pertaining to murders of Honduran women in Mexico during that same period.

Around these parts, there is a macabre phrase one hears too often: Es de bar la muerta. The body was a bar girl. And just as often, the crimes are never investigated. “There’s never anyone looking for them,” Josefina says.

Ana, Broken

Rosa is resigned. In Frontera Comalapa, she learned how to survive. When I ask her why she doesn’t leave, she responds with a dispirited gesture: a forearm jerk toward the horizon. She has her doubts about everything, including Ana’s prospects of escaping to Tijuana. But if Ana stays, Rosa won’t be able to protect her from “the Mexican,” a man so violent he even beat her sister in public.

Ana says that “the Mexican” is a guy who “belongs to the group.” She talks about times when he “goes off to do those jobs” and comes back. What she knows is enough that she would rather risk leaving than risk staying.

Once, when she was spending a few days with her sister, Ana went out to buy some groceries. At the market, she felt suddenly threatened, and had an episode of memory loss. She returned without her grocery bags. “She forgot them, and only realized it when I got home,” Rosa says. They went back to the market and the bags were there, in one of the aisles.

Ana had been living in a state of shock. “Broken,” as Josefina says. Until the morning she announced to Rosa: “I bought the tickets already. They told me the bus goes non-stop to Tijuana.”

The Butterfly Girl

Cony is another victim. A survivor. She no longer works in bars, and no longer plans to escape Frontera Comalapa. Her testimony fills the gaps in Ana and Rosa’s brief accounts. As she describes the details of the business, her children come over to cuddle her; we’re talking on the large patio of her house, one day in December 2021.

She tells me how she was taken by her recruiter, a “friend” named Manuel, from her neighborhood of El Edén in Choluteca —a city in southern Honduras— and delivered to a boss nicknamed La Chica Mariposa, the Butterfly Girl; it was January 6, 2009. “Are you the one who’s leaving? Wait for me, I have to go get three more girls,” she told Cony when they met. “I’ll come back for you in about three or four days.”

The Butterfly Girl left on her Vespa scooter and headed toward the town center, Manuel vanished, and Cony waited until the woman returned with the other girls.

Her account of their journey to Mexico is identical to Ana and Rosa’s: the Congolón bus bound for Guatemala, a hotel in the center of the capital city, their arrival at La Mesilla, the dirt road to cross into Mexico, the Pan-American Highway, Frontera Comalapa.

They were going to work at a bar called El Herradero. When they arrived, there was tension in the air, because the owners had been expecting eight girls, but were only delivered four.

On January 8, they knocked on the door of the Butterfly Girl’s house. The girls were sleeping on the floor. They all woke up. It was the men, the bosses. “We’re here to inspect the merchandise,” they said. The owners of El Herradero were “wasted.”

“The girls are tired now, come back tomorrow,” the jefa told them. “Show them to us,” the men ordered. The four women got up from their mats and filed out into the street. “They saw us, but then she brought us right back into the house,” Cony recalls.

On their second day in Frontera Comalapa, they were forced to wash the Butterfly Girl’s clothes by hand while she watched them, lying on a couch. “There were so many clothes,” Cony says. “She said if we were hungry, we needed to earn our meals.”

Cony remembers how La Chica Mariposa would wander around the house with a large tattoo on her back: a brightly colored butterfly. She was in charge of keeping the women captive, convincing them they couldn’t leave, and she spent the bare minimum on expenses; the business had invested 4,000 pesos each for their transport from Honduras, and the Butterfly Girl was tasked with collecting this debt. There would be no money spent until they paid it off. The only items she gave them for free were the soap and shampoo they would use before being taken to the bar.

That night, the transformations began: “Go to the bathroom and get yourself ready,” the Butterfly Girl commanded. Cony’s curls disappeared; she left for work with straightened hair, false eyelashes, and heavy makeup. The bun she had always worn back home in Honduras was gone.

They headed toward the park in the center of town, crossed through it, and arrived at the bar. “When I sat down at the table I saw all the girls. They were all so pretty. And all from Honduras. One of them was from Santa Bárbara. Her name was Xiomara. She was really beautiful.”

Xiomara passed her a napkin with her job instructions. “Don’t get separated from me, I’ll take care of you,” she told her. With a snap of his fingers, one of the owners ordered Cony to attend to the first customer of the day. “Don’t give him a sad face,” he warned. “You have a debt to pay.”

That day, Cony tasted beer for the first time and learned how to fichar —to waitress on commission— but her “sad face” never went away. Her salary was 300 pesos a week. If she wanted to earn more money to send to her mother and children, she had to drink with the customers. The more alcohol they consumed, the more the business profited, and the higher her commission.

Sleeping with clients meant higher pay, but how much higher depended on how well they satisfied the customer’s demands. Cony says she never acquiesced to doing that.

On her first day of work, a man with missing teeth came to the bar. Despite all the time that has passed, Cony still remembers him clearly, with disgust. He went straight to the boss and asked for Xiomara. “They’ve already paid for you,” the owner said, ordering Xiomara to “attend” to him.

The eyes of the other young women followed Xiomara until she disappeared into the small room.

When she came out, the girls examined their companion: “Hey flaca, you still have your lipstick on,” one of them marveled. They were relieved when Xiomara told them that, even if they slept with the clients, they could refuse to kiss them. Then she stuffed some bills into her bra.

“I’m all alone, where could I even run off to?” Cony thought. One day, the owner taunted her: “Hey, want to end up sending money to my mother-in-law?”; that’s how she learned that he slept “with all the girls who came through.”

Cony chose the long route: earning extra money by drinking with customers. She was paid 15 pesos (less than 1 dollar) for each ficha, which means “chip”; traditionally, ficheras would earn chips and exchange them for cash at the end of their shift. “I was going from one guy to the next. I was getting drunk, and they were getting rich,” she said.

Two months after arriving in Frontera Comalapa, she was able to rent a room next to the Telmex cell tower in the center of town, near the leather shops, and close to the bar.

In that space, now her own, she was free to invite Xiomara over to cook “frijolitos” and watch soap operas. One day, they both received a “work” proposal that would bring them a little closer to home. Waitressing at a bar in Guatemala. So they fled across the border.

The day after they left, at six in the morning, the Butterfly Girl was screaming outside the hotel where they were sleeping: “Those two old hags are mine, I already paid for them to be brought to Comalapa!” In less than 24 hours, the girls were back.

Escaping Frontera Comalapa is not so easy.

Cony worked in different bars in the municipality for eleven years. She considers the Mexican state to be an accomplice to the crime of trafficking of which she was a victim, because instead of protecting her, FGE agents were her clients.

“Some of the men I saw [in the bar] were from the prosecutor’s office,” she says. “It would be great if they’d break up the trafficking networks. The guys from the fiscalía are always smacking women on the ass. The ones from the Ministerial [the State Attorney General’s Office].

“Here, in the bars, it’s always the guys from immigration and the prosecutor’s office who try to put their hands all over you,” Rosa says, waiting to meet her friend Daniela’s new baby at the birth house.

There is a gap of nearly ten years, from 2009 to 2018, separating the events narrated by Cony and those recounted by the two sisters, but in both cases, their testimonies identify Mexican officials as accomplices to the crime of trafficking.

One February 14, Cony remembers, her boss showed up with thongs for all the girls, because he wanted to organize a runway show for Valentine’s Day. They would make even more money from the clients, he told them.

That was the day Cony ran away forever. No one came looking for her. Her lifespan as a fichera had run its course. She even stuck around Frontera Comalapa and started a family.

The Butterfly Girl kept up her illicit business. In 2020, she ran into Cony on the street and let out a “You look so pretty!” that reminded Cony of her ex-jefa’s cunning manipulative arts.

“No one has dared denounce the Butterfly Girl. She’s still here. That woman is still living here!”

Wall of Corruption

Sister Lidia Mara Silva de Souza has spent twelve years combating human trafficking as a member of the Scalabrinian Mission, mainly in the cities of San Pedro Sula and Tegucigalpa. Through her work, she has learned that in Honduras, the secrets of the trafficking underworld are protected by an impenetrable wall of corruption designed and fortified in courtrooms and prosecutors’ offices.

“We have found that public officials are involved in trafficking networks. These crimes aren’t investigated or prosecuted because [the owners] are political figures, big businessmen, people with a lot of influence,” she told me in 2021, after assuming her new post in Mexico.

In 2010, the Scalabrinian Mission opened a shelter in Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras, for women victimized by traffickers while migrating. That same year, an envoy from the national government asked them to stop combating trafficking “because there were judges and high-ranking officials in the country involved,” Sister de Souza says.

They ignored him and continued their work. But the threats kept coming. “We would receive calls telling us to shut down, making threats against our staff, [asking] us to hand over women,” she says.

The phone numbers were always private, the location of the caller concealed. “How could it be that right after we started our work there, from the very first case we had, calls started coming in from a non-public number? It was a clear sign of the corruption in the system.”

According to Sister Lidia Mara, Honduran government institutions are another link in the chain of human trafficking.

They went from targeting the shelter in Tegucigalpa to threatening another in San Pedro Sula, founded that same year. This time, the warning was brutal: they dumped a body at the front entrance, with a message demanding they hand over the young women they were protecting, or else the next victims would be the nuns themselves.

To send the message, the criminals needed a corpse, so they killed a random person. No more details were reported about the homicide, says sister Lidia, because in such cases, “not knowing” is a matter of survival.

This was the definitive threat. The project was shut down and trafficking victims were left with no refuge. “We had no way to protect them. We already knew it was [because of] corruption at the Ministerio Público [Public Prosecutor’s Office], the people who were supposed to protect us. It was a very, very difficult situation.”

Sister Lidia Mara is also a survivor; anyone who investigates trafficking in the region, and doesn’t die trying, is one too, she says. “The whole time I’ve been in Honduras, my life has been at risk because I’m involved in fighting human trafficking.”

In an interview conducted in 2021, when Rosa Corea was still director of the Inter-Institutional Commission to Combat Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Trafficking in Persons (CICESCT), Corea acknowledged the involvement of Honduran public officials in the business of human trafficking, echoing the claims of the Scalabrinian Sister.

“They’re officials of different ranks, but mostly it’s the agents at the borders. The employees have certain posts, and from those posts, they facilitate the operations,” she says.

Regarding control exercised by organized crime over the trafficking networks in Frontera Comalapa, Corea says it’s “something people talk about.” “If you go through the missing persons records in Honduras, and look at the entries for people who took that migration route, the numbers are very high,” she asserts, “so there is certainly a high probability that this is happening.”

According to the most recent Analysis of Missing Persons in Honduras published by the National Police, of the 940 missing persons registered in the country in 2022, 38 percent were women. The municipalities with the highest number of registered cases were Distrito Central (44 percent), encompassing the capital city of Tegucigalpa, and San Pedro Sula (11). The majority of disappearances took place at homes (39) and on public streets (33); only 17 percent occurred in “unspecified” places.

At the end of last July, the National Human Rights Commissioner reported more than 1,900 cases of women and girls who had disappeared in Honduras between 2018 and 2022.

The former director of CICESCT agrees with the assertion of IOM officials interviewed for this report that those involved in these networks in Central America are traffickers, and in Mexico, members of organized criminal structures: “The fact that our countries are not capable of finding and catching these fifteen or seventeen people [who run the trafficking network] is very worrying,” Corea says.

In 2012, the Scalabrinian Mission determined, based on witness testimonies, that the trafficking corridor is connected to established migration routes, which in turn are also used by drug traffickers.

“Unauthorized migrants are often forced to participate [in transporting drugs] and to provide information [to the criminal organization],” says Sister Lidia Mara. “These routes are very active. It’s easy to recruit migrants because they are already in conditions of vulnerability.”

San Simón, Sinner and Savior

It smells strange in the bar: a mix of cleaning products and spilled beer. The floor is stickier behind the chairs than under the tables.

“When a client goes to the bathroom, we dump our beer out behind the seats,” says a woman who works there. The bartender suggested the trick for their own protection: the less alcohol they drink, the more able they are to control the hands of the patrons.

The women shoot regular glances toward the bar, where a foot-tall figurine sits perched on the counter. It’s a man with a cigarette in his mouth, surrounded by more cigarettes and some small glasses of tequila and incense. He is sitting on a small chair, holding a bag of money and wearing a suit and a brimmed hat. His mustache is reminiscent of Jorge Negrete’s. He is known as San Simón. “El Moncho,” they call him in Frontera Comalapa.

This Guatemalan saint — not recognized by the Catholic Church — is a protector of “broken people,” explains anthropologist Blanca Mónica Marín Valadez, a doctoral student in Mesoamerican Studies at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, who has researched the cult of San Simón in Guatemalan bars.

The image of Moncho is that of a drinker and a sinner. A saint who protects and does not judge.

Local authorities realized that eradicating prostitution would be impossible in Frontera Comalapa, so they established a “tolerance zone” near the town’s main entrance, just 100 meters from the municipal hall.

At one of the bars in the zone sits San Simón. They keep him behind the counter. He looks clean and well kept. They don’t neglect him. They fear him. “He gets very jealous,” “he’s always watching us,” “he takes care of us,” the women at the bar say.

Some of them came to work at the bar of their own accord, after leaving jobs at establishments controlled by organized crime. Others were forced here by “a series of circumstances.” They are all paid for their work, and can speak and express themselves openly, Josefina says.

There are several bars in the zone, all located on the same piece of property and regulated by municipal codes. This, for some reason, keeps the criminals away.

“The zone is a very interesting place that welcomes a lot of survivors of sexual abuse,” says Marín Valadez, the anthropologist, sitting at a table with a woman in her fifties, who first came to Frontera Comalapa years ago. “There are safe houses where women are enslaved,” she adds.

The two women talk about El Moncho; his day of celebration is October 28th. They talk about how he awakens a “rabid” devotion in them that they express by living life to its limits.

“They escape the gangs and come here, where they’re free to charge for their services,” explains Marín Valadez. “In a certain sense, they’re also trying to redefine their work. They practice prostitution because they want to give their children a good life.”

San Simón arrived in Frontera Comalapa together with the population of Guatemalans forcefully displaced by the country’s internal armed conflict. The municipality is one of four main areas in the region that began receiving thousands of refugees from Guatemala in 1980. According to the Mexican Commission for Refugee Aid (COMAR), in 1983, there were more than 40,000 Guatemalans living in Chiapas.

“One of the most important contexts for understanding Comalapa,” says Marín Valadez, “is the Guatemalan war, which disrupted a lot of things here.”

The region, she says, “has more of a connection with Central America than with central Mexico,” given its porous border with Guatemala, easily crossed using eight official ports of entry or via countless illegal routes along rural roads.

Organized crime, she adds, has taken root in the area, which suffers from “a major institutional vacuum” that has made it easier for criminal groups to take control of the territory.

“People learn to live with the drug traffickers; they establish relationships with them. It’s not that they’re dedicated to the drug trade or are pleased with the situation; they just know that they need to do business with them to survive,” she says.

San Simón accompanies “los otros,” “the others,” the “broken” people, in places where there is “a social fabric with deep-rooted conflicts.” Organized crime, violence. People forced to “live on the periphery,” the researcher says.

The cult of El Moncho is also an attempt at healing, she adds. The women here want to recover and are looking for the right path.

Babies with No Birth Certificates

It’s November 2021, exactly 24 hours before Ana and Rosa’s friend Daniela will deliver her son. Fifteen midwives are gathered in the courtyard of the birth house, talking and eating grilled chicken with tortillas and beans under the shade of a mango tree.

Ariadna has worked as a midwife for more than twenty years. She says her biggest concern with “the migrant moms who are living here out of necessity” is that they face too many obstacles when attempting to legally register their children. “They shouldn’t discriminate against them! Children born here are Mexicans and should be given birth certificates,” she says.

Fabi, another veteran midwife, hasn’t had to struggle as much to get the Civil Registry to validate her birth certificates. She says she feels relieved, because for years “the doctor at the health center would tell us that they wouldn’t admit Central American women.” Now that they can, her main concern these days is that so many pregnant women from Honduras suffer anemia.

Dorotea has been a midwife for 45 years. Less than a week ago, she says, two Honduran women came to her seeking help with labor, and immediately after giving birth, left with their babies and never came back. “Every month I see at least one or two Honduran women. They only come for one visit.”

She can’t remember the first year she started seeing Honduran women who work in bars, but she tries to think back: “I saw two patients who worked in bars. Their children have grown now; they would be about ten years old.” In other words, sometime around 2011.

“They come here to have their babies, and the next day, or the day after that, they’re gone. A day’s rest [after childbirth] is very little, but the bar owners just take them away like that. Once they’re gone, we don’t know what happens to them,” says Claudia, another midwife who lives in Chamic.

Women from Central America who have been living in the area for weeks, months or years come to see Claudia at her home. They come for brief, one-day visits, to “position the baby,” massage the womb, or, when a woman shows up in active labor, to deliver the baby.

Sometimes they’re accompanied by an older woman who “employs” them at a bar. Or by men whom Claudia would rather know nothing about. For her own safety.

Dorotea, the most experienced of the group, closes the conversation. Before picking up the Styrofoam plates and leftover tortillas, she laments the state of affairs in her home town of Frontera Comalapa, where criminals operate with impunity, but when she accompanies a Honduran mother and her newborn baby to apply for a birth certificate at the Civil Registry, she faces rejection and accusations: “They accuse me of selling certificates.”

The women who work in the bars, she says, don’t seek help from doctors; they go to the midwives. “They talk about how they left their homes because there’s no work, how it’s hard for them to feed their children, how there’s a lot of crime and violence,” she says.

At the time of our interview, Dorotea estimated that fifteen children with no birth certificates had been born in her home. One is already five years old.

Nich Ixim, an organization based in San Cristóbal de las Casas that brings together more than 600 midwives from different parts of Chiapas, says that in Frontera Comalapa, an average of 40 “migrant babies” are born each month without birth certificates. They are delivered by midwives, in their homes and on their beds, with what few resources they have. They are also born in secret, in impoverished households in rural communities.

We asked the Mexican Social Security Institute and Ministry of Health how many Honduran women received medical attention during pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum between the years 2010 and 2022, both in Chiapas and Frontera Comalapa. Once again, they did not provide any information.

As the meeting winds down, the midwives talk about their tradition of spreading the placenta over a piece of cardboard to form the image of a tree of life, or of using two pieces of cardboard to press the placenta into the shape of a butterfly with spread wings, its body bursting with purple, red, violet and pink. It’s a small ritual in celebration of life.

The Escape

There is no tree-of-life or butterfly ritual for Daniela. The placenta is sealed in a plastic bag. In the courtyard of dry earth strewn with small river pebbles, under the shade of the mango tree, a boy digs a hole to bury it.

From the room where the young woman gave birth come the cries of a newborn and a voice responding with comforting coos. Outside, Ana and Rosa talk loudly, laughing over some anecdote or cursing the fate that uprooted them from their home country.

Three Honduran women with children born in Mexico. Three victims of human trafficking for the purposes of sexual exploitation.

That same day, Ana is getting ready to leave on a 2,602-mile journey through Mexico, destined for Tijuana; she is preparing to spend 46 hours on a bus with her two children: the eldest with his refugee application, the baby born to a midwife in Mexico.

“I can’t take one step without him noticing, but I have to try,” she says, referring to “the Mexican.”

The next day, Ana flees with nothing but a backpack. With no papers proving permission to be in the country, the only document she carries is the birth certificate for her Mexican-born baby, which was provided by her midwife. She hauls her daughter on her hip and the little boy walks behind them.

The most difficult part is leaving the community of Chamic — escaping the radar of her “partner.” After an hour’s journey by bus, they arrive in Comitán and make it through the migration checkpoint at the entrance to the city, where bus inspections by INM agents are notoriously fierce.

They pass through Comitán, leave San Cristóbal de las Casas behind, and head toward Tuxtla Gutiérrez, the capital of Chiapas. This is their first goal: to make it to a big city where they can be relatively invisible, and hopefully beyond the reach of their abuser.

Passing through a toll booth shortly before arriving in Tuxtla Gutierrez, the bus is stopped at a temporary migration checkpoint. She shows the agents her baby’s birth certificate, but they refuse to accept it. The agents pull her off the bus with her children and leave them stranded on the side of the highway.

Ana sends messages on WhatsApp asking for help, then takes a bus back to San Cristóbal de las Casas with her children, where she rents a room for the night in a small hotel. We meet the next morning at the entrance to the city; she’s sitting at the foot of the statue of Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, eating cookies with her kids. We go for some steamed carnitas tacos.

Ana decides to present herself at the INM offices in San Cristóbal to request a Mexican transit permit. A civil society organization in Chiapas, Formación y Capacitación (Foca), offers to host her. We say our goodbyes.

Later, I send her a few messages on WhatsApp. Days pass without any response, then she tells me she’s back in Frontera Comalapa; she sends an emoji of a crying face, with a pistol pointed at it.

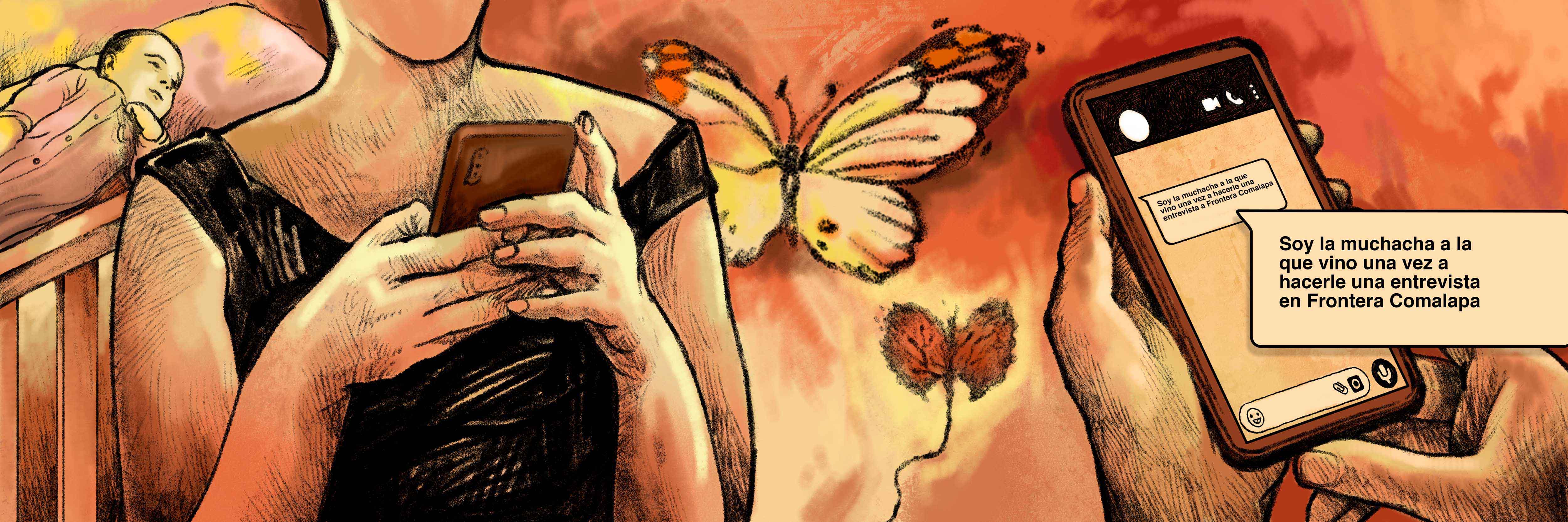

A year later, on November 2, 2022, I get a message from a faraway place on the north end of the continent. It’s a number registered to a certain “Madre Soltera” (Single Mother): “I’m the young woman you interviewed in Frontera Comalapa a while back,” it reads.

It’s Ana. She’s finally free.

This story was published by Quinto Elemento Lab in editorial collaboration with El Faro and with illustrations by Brunóf. Translated by Max Granger.

Súmate a la comunidad de Quinto Elemento Lab

Suscríbete a nuestro newsletter

El Quinto Elemento, Laboratorio de Investigación e Innovación Periodística A.C. es una organización sin fines de lucro.

Dirección postal

Medellín 33

Colonia Roma Norte

CDMX, C.P. 06700