Mexico hell, again: Survivors among the disappeared

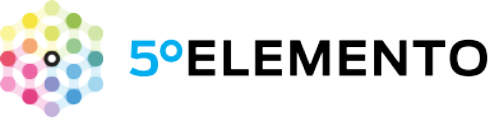

The Jalisco New Generation Cartel offered fake jobs, then enslaved them and held them by force. Now they’re foot soldiers for organized crime. They’re alive, but off the grid—completely disappeared. A survivor recounts his days in hell.

By Alejandra Guillén and Diego Petersen / A Dónde Van los desaparecidos - Quinto elemento lab

February 4, 2019

“When I escaped I went far away because wherever they spotted me, they were going to kill me. I thought if I went directly to the authorities, they’d hand me back to the cartel. After a while it came out in the news that someone was in the same boat as me and he got up the nerve to call. I’d said the reason I fled from them up there was to try to offer some peace, some calm, to the people who’d lost track of loved ones. A lot of them are the ones I saw get calcified, and no one in their families knew how they died or disappeared—unless I spoke out. So I’m going to stick out my neck and tell my story, to bring a little peace to their families, so they’ll let go of thinking they’ll find them. I got in touch with the Jalisco State Prosecutor’s office and I told them that I, too, had been robbed of my freedom in the Navajas sierra, by the Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación (“the Jalisco New Generation Cartel;” acronym in Spanish: CJNG) and that I could identify seventeen “disappeared” I saw die before my eyes, at the hands of our captors.”

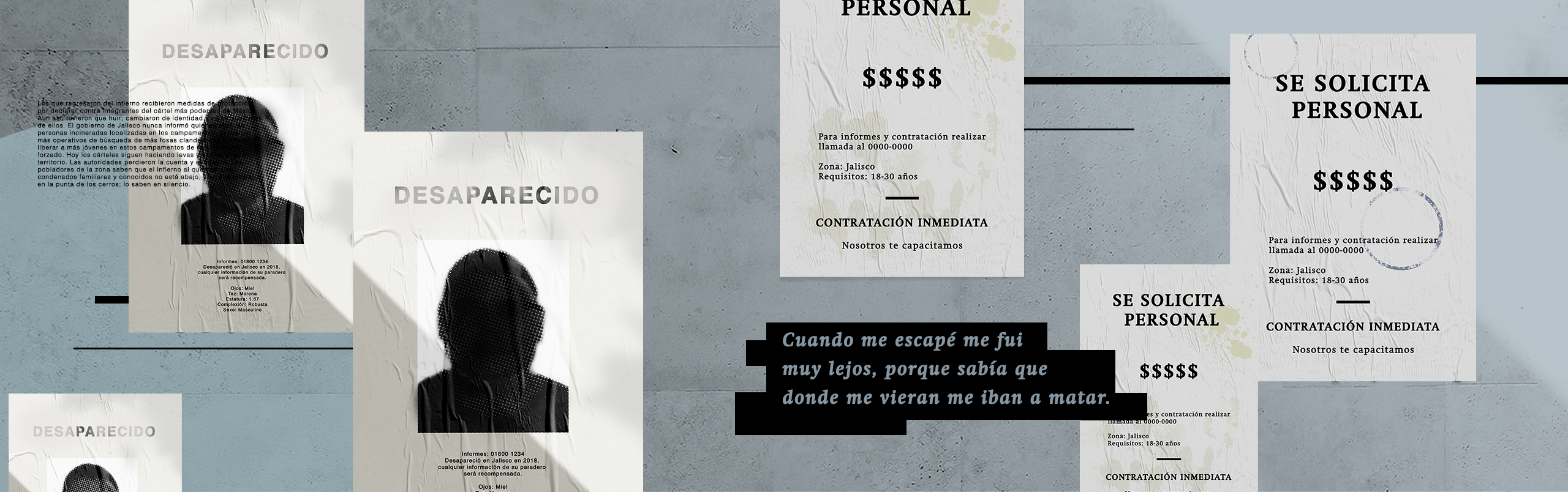

Luis (all names false to protect witnesses and other parties) is a survivor of encampments where the cartel forces young men to train as sicarios (i.e., street-level assassins, hit men). At the start of 2017, he was working at a rehabilitation center. He couldn’t make ends meet on the salary there and he wanted to get away from addictions and the addicted. He went on social networks to look for new work. In April that same year he joined Facebook pages listed as “GDL (i.e., Guadalajara) Jobs Exchange” and “Guadalajara Jobs.” He got word of the job offer in a e-message: 4,000 pesos (about $208 USD) weekly as a security guard. He contacted the woman who had messaged him and she asked him to get in touch with Mario, the supervisor at the hiring company. A week later they added him to a WhatsApp group along with fifteen other people who were interested in the job. They were asked to come to a training in the municipal jurisdiction of Tala and they’d be paid the first 4,000 pesos in advance.

Luis was fully on board, ready to work. He never thought that when he showed up for his first day of work they were going to throw them all into safe-houses and then take them up to camps in the Ahuisculco sierra. But not to kill them. It was to train them and force them to work for the CJNG.

Some of the families reported their members’ disappearances, not knowing they were alive but in the hands of organized crime. The Jalisco Prosecutor’s office carried out operations in July 2017 and discovered the training camps. In one raid they arrested fifteen men of whom three identified themselves as missing persons and could prove they’d been held against their will. They were freed and their statements were archived in case-file 1611/2017, as was Luis’s statement.

Thanks to their testimonies and other anonymous accounts, it’s now known that dozens of men from valleys in Jalisco’s Tequila region, the greater Guadalajara area, other Mexican states and even Central American migrants had been transported to the Ahuisculco hills; and that slavery and forced labor had been a CJNG modus operandi used to assure business went smoothly.

Among the “recruits” about which we have some record there were day-laborers, some unemployed, car-washers, handymen, porters at wholesale markets, deportees, former cops, former members of the military, young men who were fresh out of addition-rehab centers. One survivor even recounts in his testimony to the prosecutor’s office that he was walking at night in downtown Guadalajara, felt a blow to his head and lost consciousness. He woke up in a safe-house.

When the prosecutor’s office carried out the raid, Luis wasn’t there anymore. He’d escaped. Later he decided to break his silence, despite the risk it might imply.

—“When they contacted me about the job, I asked if everything was legit. ‘See here, if it were illegal we wouldn’t send you to train to carry a gun. Relax, it’s all legal.’ Then I said to him, ‘But, I mean, it’s really going to be ok? My mom’s sick and I need to be able to reach her.’ That’s when Mario said he really liked me and that I was going to be going in with his recommendation. I got a cab to head out to the Periférico ring road. Ten minutes later a car shows up. They asked me if my name was Luis; I said yes. I got in and then we went to pick up another kid. We went into this really sketchy part of town. A fair-skinned guy, with a beard, comes out. His hair’s a little bit curly, he’s kind of chunky, he has green eyes. Now I know his name is Ignacio. Two women came out to tell him goodbye; they stayed in the doorway until we drove off. I could see the driver was nervous, chain smoking. I tried to make conversation and he told me he’d only been on the job barely a week but they hadn’t paid him for the previous trips. It was the first of May. They left us by the side of the highway and then a pick-up truck came by with three other guys who’d come from Mexico State. One had a glass eye and the other one was skinny, with a fake leg, and the third one was fat, with this hair-tuft on his forehead. The driver was this obese pig who barked at us to get into the payload. On the road we figured out we’d all five been on WhatsApp the day before and we’d been contacted by the work exchanges we signed up for on Facebook for the job as body- or security guard for 4,000 pesos a week. It was a nice salary for what I needed,” Luis recalls.

“They switched us to another car. We turned off to go to Tala; then we went through a gap and got to an abandoned farm, with barbed wire and wooden-stake fences; there was a guy holding a cuerno de chivo—‘a goat horn,’ i.e., an AK-47 assault rifle—who told us to follow him inside. I saw there was no furniture, just people on the floor; 38 piled in, on the ground. That was when I knew I was in trouble, because this wasn’t normal. When we came in they ordered us to stay silent and sit, telling us we couldn’t even go to the bathroom without asking for permission. Everyone one of us was poor, downtrodden. Some people looked like really tough characters and others wore expressions that said they had nothing else to lose in life. I copped to the fact I’d gone past the point of no return and maybe something terrible was going to happen. And I started to smell this weird stink. You could see the sorrow and misery in people’s faces.”

Through job advertisements on social media, the CJNG deceived men of different ages to join the ranks of its armies. Many of their families reported them missing, unaware that they were alive in forced labor.

A well connected boondocks

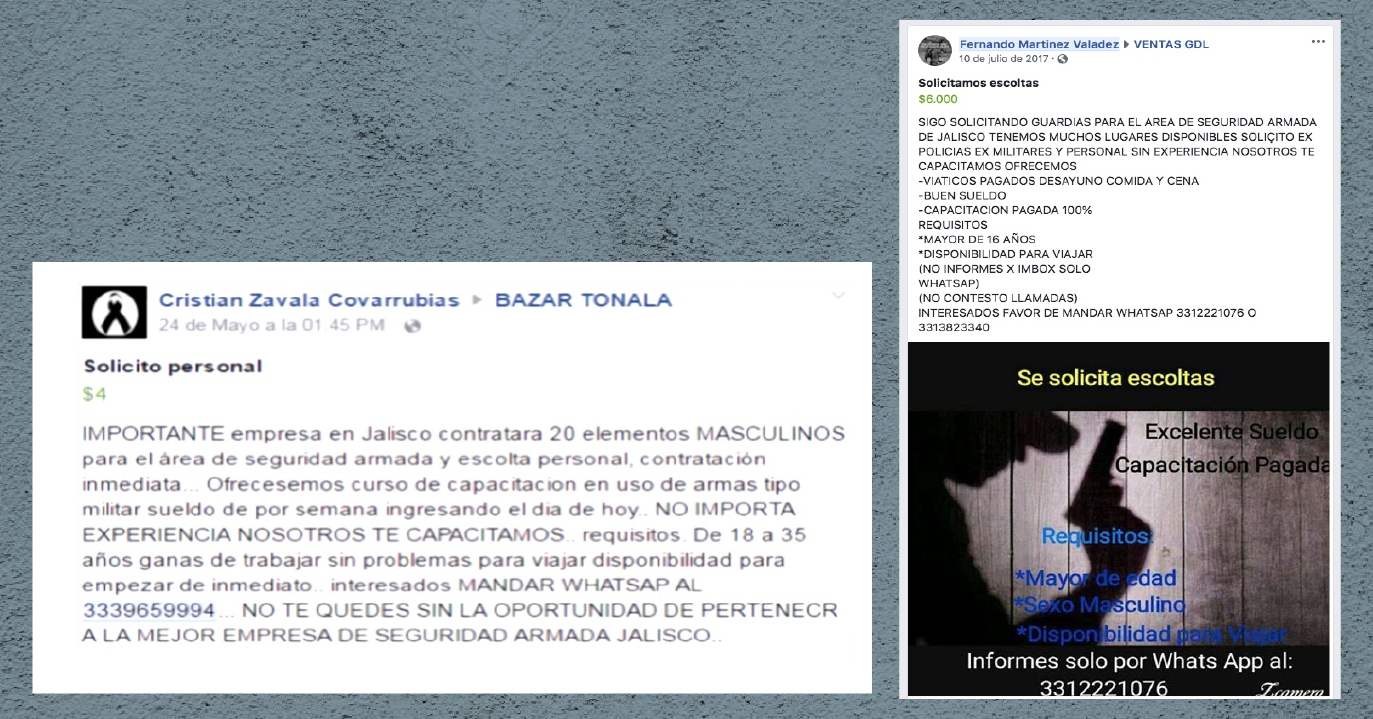

Tala, Ahuisculco, Las Navajas and Cuisillos are villages less than an hour out of Guadalajara, right behind La Primavera forest. You get there on the less-trafficked, non-toll road to Puerto Vallarta. After getting through the forest you have to turn left and head into the Ameca River valley, where you’ve got cultivated fields full of sugarcane and old haciendas. After Tala, the next municipality is Ahuisculco, an ancient indigenous community that still stewards the forest and protects its water sources. The town is in the foothills of the mountain range of the same name, a volcanic formation that in fact is the continuation of La Primera forest. On the other side of the ridge lies the town of Las Navajas, where, the residents of Ahuisculco say, “crime had come in; people accepted things that ended up ensnaring them.”

The town of Las Navajas gets its name from major obsidian deposits in its soils, obsidian that centuries ago was sold in the form of knives—navajas—to regional indigenous communities. When you move through the town, there’s a gap that heads into the hills. The road is home to one of the safe houses survivors mention and that the Jalisco state prosecutor’s office seized. Further up, there’s a place called La Reserva, a ranch local sierra residents say belongs to one “Don Pedro,” the name by which they knew Rafael Caro Quintero. They say Don Pedro came at the end of the 1970s, planted marijuana, grew wildly fat, and rich, and took control of the area. Even following the Jalisco prosecutor’s operations, in July 2017, SUVs and young men—known as halcones, i.e., “falcons”—on motorcycles continued to patrol the road. This is the gap all survivors mention in their testimonies as the way up the mountainside.

These mountains, unnamed on maps, are strategic for reasons of connectivity. On one side you’ve got roads leading to the highway to Colima and the coastal city of Manzanillo; on the other side lies the Sierra Madre Occidental mountain range, that leads to the Pacific coast and Puerto Vallarta. Chemical precursors to synthetic drugs enter through the Port of Manzanillo and reach Colima via the highway; before getting to Guadalajara they take a road called the Circuito Sur (also known as the Macrolibramiento) that puts them just a few meters from Las Navajas, through which they go into hills that serve as a hideout that encompasses camps, burial pits and narco-labs. Via Cuisillos they can reach the highway that takes the drugs to northern Mexico, Mascota or Puerto Vallarta.

On 29 July 2017 the Jalisco public-prosecutor’s office announced that between 6 and 13 June they had received six missing-persons complaints. Each missing person told someone at home they had gone to Tala because they had found work as survey-takers, bodyguards or local police officers.

Mother's accounts

Laura reported her son Ignacio’s disappearance on 22 July 2017. They asked her if she noticed anything strange during the last days she saw him.

“He was beside himself because he wasn’t working,” she said. He was 22 and weighed more than 100 kilos, had light brown hair, green eyes and a tattoo on his forearm. A high-school dropout. He told his mother he’d found work as a private security guard where they’d pay him 4000 pesos weekly. He had to go to Tala for two weeks of training. On 1 May they picked him up at his house in a working-class neighborhood south of Zapopan.

Ignacio set out with a black-and-gray canvas backpack, fastened with laces, in which he’d packed three days’ change of clothes: boxer shorts, socks, a wood brush, plastic flip-flops, some white sneakers for working out. He didn’t have a cell-phone and they wouldn’t let him take one anyway. His mother and sister came outside to say goodbye. He got into a light-brown car, with two other men inside: the driver and another young man they had just picked up; it was Luis. They never heard from Ignacio again. Two months later, the sister saw on the news that they’d found enslaved people in Tala. That was when they reported his disappearance.

Ernesto was also reported as having disappeared. A big guy, 1.78 meters tall, weighing 96 kilos, with a round face and light brown eyes, no tattoos and with bite-scars on his chest and left arm, he had on black-denim jeans and a light-blue polo shirt. He was 26 and in dire need of work. He’d become a father in early 2017 and had no steady income. He was desperate when he found an online job offer. They contacted him on 30 April. The following day he went out early, just before seven in the morning; they were going to pick him up at the Periférico ring-road, at the corner of Mariano Otero, and then move on to the training at Tala. He told his mother and his wife that he’d be in touch after a few days. Karla, his wife, called him at ten in the morning to see how everything was going; he said they hadn’t gotten there yet, but as soon as he could he would send them the telephone number at the training facility. He never sent it. They’d promised him he could go back to his family every week. He never returned. Rosa, his mother, reported his disappearance on 8 May 2017.

This safe house is located across the town of Las Navajas (Tala, Jalisco); officals found the camps where young men were forced to train as 'sciarios'. Photo: Raúl Torres

Getting ahead means using your head

During the time Luis was trapped in the first safe-house—May 2017—he started to observe the people who were watching over him. He discovered that some of them had been captured, like him, but had been able to go on furloughs called “vacations.”

—“I know this because I saw who was in charge, at a higher level; that these two guys had gone and come back; that there was a hierarchy. It didn’t matter if they trusted you or not; the hardcore test to be one of them was to come back to work with them.”

He continues his account. “They pulled us from that house and started piling us onto trucks. They hauled us to Navajas via Cuisillos, to another big property that had an iron gate, like for livestock, a meter high, unfinished. There was a man in a hat, like something a farmer would wear, who shouted at us: ‘See here, you sons of…line up, get going and on the double! Does anyone know why the fuck he’s here?’ I couldn’t say anything; they’d have killed me. He grabbed his rifle and fired into the air above us. ‘I’m giving everyone here a dipshit vacation. If you come back, there’ll be work, and if not, you’re fucked. Who wants to go right now?” No one said anything.

One guy had me in a hold and shouted at me, “Get going, you brown bastard, ¡témplate!” Témplate means step up, take action, use your head. We went to the peak and got to the camp. It looked like nature camps in the United States and it turned out to be this lady’s place who rented it to the man in the hat.

Stand out to survive

The abuse and threats had begun in the safe-houses. Besides Luis, the prosecutor’s raid saved three other survivors. In their official declarations, they related how they’d been looking for work and that the “recruiters” hustled them off to safe-houses. In one such place, there were some fifty men sleeping on the floor, beaten into submission, under threat they’d be killed if they attempted escape.

—“We exercised every day and they said those that stayed in line would get ‘vacations’ or a break. They classified us as “new,” “semi-new” and “old-timers.” The new guys were beaten up all the time; armed men were always guarding over us. A week later they brought me and four other guys back in an SUV; other armed men left me in a safe-house where I could take a bath. It dawned on us there that something else was going on. I heard voices that said we were going to work for their cartel. That was when I started to get scared. Our jailers were using drugs; I’d never done them. I worked, had a family and children. On the 23rd they took me back to the mountains, to a new camp, that they had us build using wood, nylon and branches; we had to fetch water and food; they beat every inch of my body. ‘You’re not worth shit,’ they’d say. ‘Get moving, you idiot dogs.’ We weren’t allowed to sleep before midnight, and anyone who did had to be ‘it’ in a paintball match—or they just killed him. The guards plugged two guys because they went to a convenience store without permission. They ordered the rest of us to take their corpses to this inclined creek bed and they told me to chop firewood, branches, and we burned them right there. In conversation it came out they’d all been brought there under false pretenses. It was twenty of us, just like me.”

Luis returns to his own account. “They left us in a camp an hour from the town of Cuisillos (…) where they made us sleep outside, and they kept us down by saying we had to ask permission to pee, and if we didn’t they’d beat us up (…) I remember one day we were hauling stuff around and we turned at a creek bed and ‘El Momia’ said to ‘El Checo’ (who had tattoos with his daughter’s birthdate and one with his kids’ names on his neck), ‘On your knees, this is for disobeying my orders.’ He pulled the trigger and Checo fell dead. Then he shot another guy (…) They took them down to the creek bed, stripped their clothes off and followed instructions. They put them on a firewood stack with scrub and timber, set it aflame and we waited for the bodies to burn up completely.”

—“We walked another thirty minutes and got to a camp built from branches and black plastic, lined with more branches and trash. I saw there were three armed men outside. We went in and there were some twenty more men lying there. So we went back out to the camp and lay down to sleep as best we could, but when dawn broke they roused us all and lined us up; started telling us we were going to train to work as sicarios—hit-men, assassins—for the CJNG. If we resisted, they’d kill us. They started training us and made us exercise; they had paintball guns to teach us and they shot paint at us mercilessly.”

“On 24 July 2017—I remember it was a Monday— they woke us up and made us haul plastic and provisions (…) The head guy got all call that we needed to get our shit together because SUV black-and-whites where coming to make a sweep of the sierra. Three opened fire and the only thing I could do was to run to the bottom of the hill to take cover from the fire. The cops surrounded us, shouting, ‘chest on the ground, hands up!’ That was when they arrested us all.”

Forest camps were camouflaged to avoid being spotted from the air. The Jalisco public prosecutor identified hotspots in the Ahuisculco sierra and was thus able to locate them.

The three young men quoted cited the Jalisco prosecutor’s operation, through which they were freed, in their accounts. Days later, on 29 July 2017, former Jalisco State Prosecutor, Eduardo Almaguer, reported having rescued a young man and for that reason had been able to locate the camps. The prosecutor’s office estimated between fifty and sixty individuals had been guarding forty “recruits.” The whereabouts of these last were unknown.

It was not the only training and extermination camp to be found in the state. Another cell of the same cartel was detected in 2016; it operated out of the Guadalajara suburb of Tlaquepaque and in Puerto Vallarta, and had handed out flyers offering employment in a non-existent security company called Segmex. Recruits were forced to sell drugs or become sicarios.

In October 2017, the state prosecutor’s office rescued four additional individuals that had been fraudulently recruited in Puerto Vallarta. They had been employed as sales agents or bodyguards; the same cartel transported them for training in the Talpa Mountains (150 kilometers west of Tala) and they disappeared. It was then that former State Prosecutor Almaguer declared this was the same criminal cell that had operated in Tala, in conjunction with members from the Mexican states of Veracruz, Michoacán, Mexico State and Jalisco.

In July 2017, the Jalisco Prosecutor’s office carried out operations in the Sierra de Ahuisculco / Las Navajas (Tala). They located CJNG camps in which they trained young men forcibly recruited as 'sicarios'.

It's the real men they take

Young peoples’ disappearance in Tala began long before the state prosecutor discovered the camps. There are records of disappeared persons starting in 2012. One such individual is Javier Cisneros Torres. His was the only family brave enough to take its search public. Javier lived with his mother in the Tala municipal seat. His sister, Alma, remembers the day he was captured:

—“Back then my brother lived with my mother, my father had died. My brother was lying down, watching TV. He went out because the neighbors called him. He went into their house and they took him from there. We managed to spot his sweater, his glasses and his keys; there was a trail of blood from the doorway. My brother liked to look out for people, for everyone in the neighborhood. He wasn’t bad, which is proven from the life he led. We’re a poor family. He had worked at the sugar mill in Tala and he was out of work for quite a stretch because the jobs there aren’t permanent. He painted the bottoms of trees white. People say the “Talibanes”—a criminal gang from the CJNG in Navajas—took him away.

“We know about at least sixty families in Tala with disappeared people. My sister and I wrote them down, name by name. I have a friend from junior high that reached out to me one day. ‘They took my brother, too.’ He told me. ‘We don’t know what happened; my brother used to smoke pot.’ I said to him, ‘OK, whatever he was or wasn’t smoking, they had no reason [to take him]. He’s disappeared and we have to find him. If we don’t look for them, no one is going to find them.’ I asked him for a photo of his brother, in case they found his body in a common grave, since you never know if he’s alive or dead. There are all these disappeared people here and no one ever says anything.

“They take the guys that are man enough to do things; they don’t haul off just anyone (…) only the ones, in my eyes, that are capable of doing bad stuff. They tell them ‘either we kill you or you work for us.’ And I think they answer ‘work.’ I’ll be honest: I don’t think my brother would say ‘go ahead and kill me.’ I believe everyone wants to live. But here’s what I said to my mom: I’d be sad knowing he were doing that kind of thing. It scares me to think he’s working for them.”

Locally, what’s happening is an open secret. The CJGN controls Tala and the surrounding territory, so those that speak must do so anonymously. Like Eleazar, who asked not to talk in public, but rather at home, recounting that they’ve taken lots of young men from the town.

—“In 2013, we starting hearing about young men that were disappearing from the area. They were farmers’ kids, but strong, and ambitious, people that know the country, which means they know how to use guns. They were the braggarts and the boasters, the ones that liked El Komander’s music, the rowdies that partied and took drugs. We found out about a lot of cases that people went to a party and were never heard from again. It seemed like some were alive; they’d call their families, but you couldn’t find them or say anything because they were forced to work for them. They weren’t guys that wanted to get involved in drug trafficking, no, even if they liked that kind of music and all the narco-culture that has seeped into everything. In Tala, there’s a lot of work in the sugar mills and that’s why they had to be coerced into going. I think they take them to marijuana and poppy fields here in the region, or in other parts of the country, because the cell that is here is strong, believe me. They supply guys for other regions from here. I think they went through all the guys that fit a certain profile and now that’s why they’re putting employment ads on the internet, to lure in the guys from other places.”

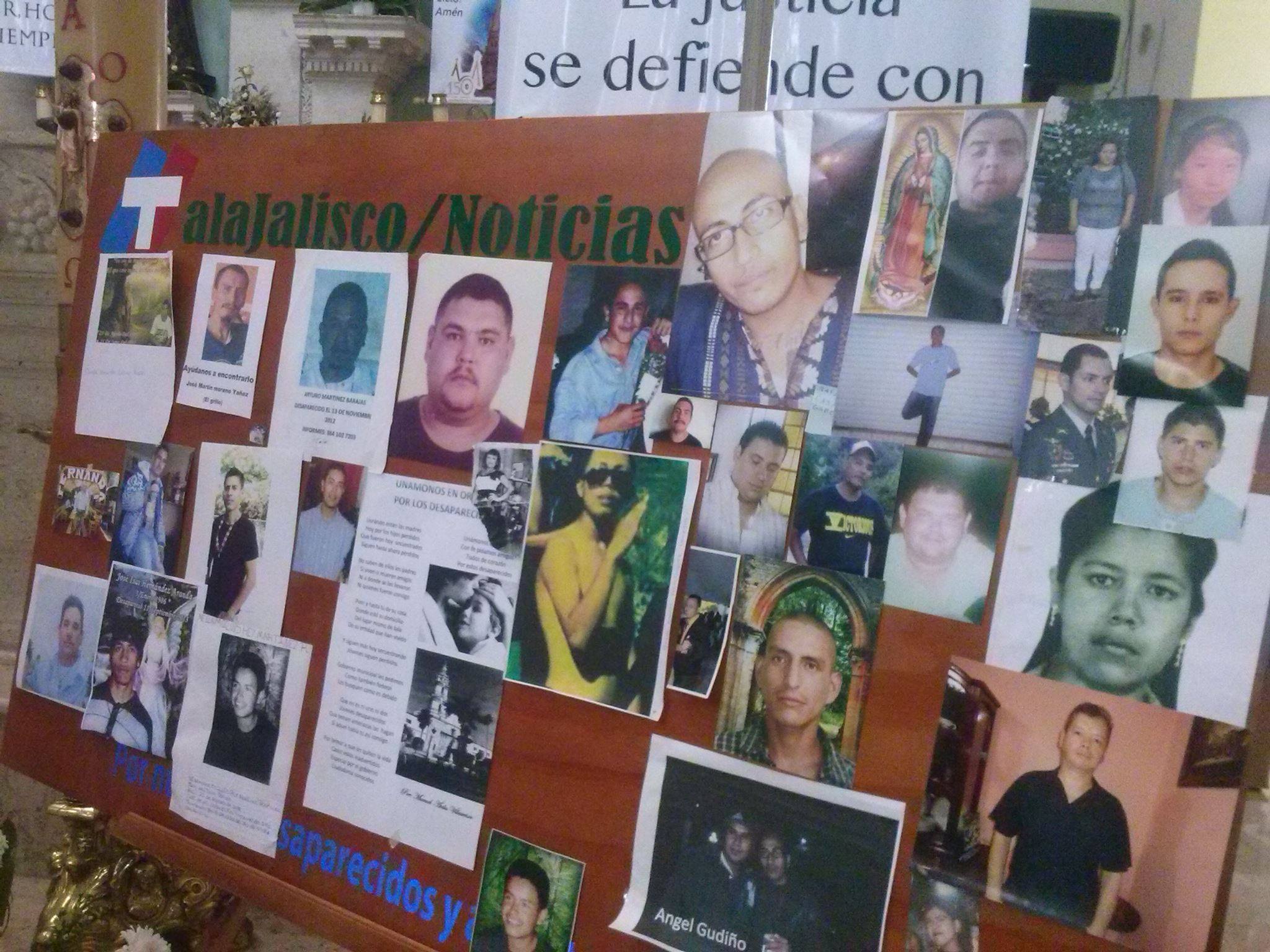

A 2014 mass celebrated in Tala on behalf of the region’s disappeared. Relatives brought photos of their loved ones. The priest who organized the service was later threatened and had to flee the town.

On 31 August 2014, there was a mass in Tala for the disappeared. Families brought in photos and loved-ones’ names, everyone was identified. Lots of people showed up. There were 35 photos on a single bulletin board, mostly men. The priest got threats for celebrating the mass and had to leave Tala

Even though a lot of families prefer not to report, according to Mexico’s National Data Registry for Lost and Disappeared Persons, in Tala there are 56 disappearance reports. Between 2006 and 2012 there were two registered complaints; fourteen in 2013 and seventeen in 2014. For locals, something was happening back then: the CJGN gained strength and took control of the area. They needed labor.

With the arrest of the Valencia brothers and Ignacio Coronel, the Milenio cartel (that trafficked drugs in partnership with the Sinaloa cartel) split into two cells. One later became Jalisco Nueva Generación, which, in October 2018, the US Treasury Department named Mexico’s most powerful drug-trafficking organization and one of the five most dangerous on the planet. The group maintains a presence in at least half of Mexico and moves cocaine and methamphetamines throughout the Americas, Asia and Europe.

They break down souls

Young people’s disappearance and consequent forced labor for narcotraffickers is no improvised affair. A Tala resident who has in-depth knowledge of the situation says that abusing them, torturing them and later making them kill and cremate their coworkers is a strategy for breaking down their souls, their inner peace, so they become yet another cartel member. They go from victims to victimizers.

In his account, Luis speaks of how, to survive, you’ve got to earn your captors’ trust. Ultimately, the cartel chooses to kill those who don’t buckle under or for whom they have no use.

—“I saw a chance to go to the head man. I was determined not to be abused or die up there if something happened. I wanted to survive. I started talking with them and trying to stand out, to earn their trust. There were gunmen everywhere. Anyone who’s trying to survive is going to have to make an impression if he doesn’t want to be abused. I began to get scared and wondered how I would start surviving in that hell. I thought I’d gone deeper with these people, to keep them from killing me, but at the same time I was putting a noose around my neck because they trusted me and they’d think I was a traitor if I didn’t come back.

“That was the worst time in my life. Around two, we’d heard El Sapo, the boss, talking. “All right! Off you go, you sons-of-bitches. Who wants to go? I’ve got 3000 pesos for you and you’re on your way home, your mother be damned.” Some began to raise their hands at that point, saying they were sure. There were three guys from Mexico State, the tubby one that came with me and whose name I now know was Ignacio; the two sad bastards from Durango; this seventeen-year-old from Guadalajara; a former cop from Zapopan; others whose names I didn’t know; and El Catracho, who’d come back from ‘vacation.’ In fact, El Mojo asked him if was sure about raising his hand and he said yes—that he wanted to see his son in Honduras. El Sapo said, ‘there you are, you’ll get there faster.’

I can remember them all, fourteen in total and he sat them down in a shack in front of the sleeping quarters and told them not to move. Then this gray Cheyenne arrived with US license plates and two guys carrying semiautomatic pistols stepped out. One was El Greñas (this kid, 20 or 21, baby-faced, who was El Sapo’s right-hand man) and he shouted out to the ones who wanted to leave. ‘OK, let’s see, you sons-of-bitches, fight it out—everyone against everyone!’ and they started fighting; whoever fell was going to die. The first to fall was one they called La Jaina (short, 1 meter 70, with a big nose and a wide face, fair, with all this hair everywhere, a homeless guy from Guadalajara), knocked down from a blow to his knees. They shot him. Then there was El Guachito, tall, with a prominent nose; when he saw they were going to take him out, he screamed, ‘Nooo!’ and waved his hands in a gesture of defense. They plugged him twice. Then came Nopal, Toño, Chucho and El 18; they opened fire on all of them, including the former cop.

In the end there was just this seventeen-year-old kid with his hands between his legs, his head crouched down, trembling. They went over to him to check him out because he was still alive. El Pitayo told him, ‘Those faggots said you said you wanted to go.’ Really shaken up, the kid responded, ‘Yeah,’ and then pleaded, in tears, ‘It’s just I want to see my little sister and my mom.’ They shot him. The dead included Ignacio, the guy that had come with me the first day, and Ernesto. They shot the taco guy in the back, making it fifteen dead. Those of us who, from fear, had indicated we didn’t want to go, were made to carry off the bodies. It took an hour and a half because some of them weighed quite a bit. We had to drag them and then echarlos a los elotes,” i.e., incinerate them.

The killers and those left behind would use ditches between the pine and oak trees that rainy-season erosion had carved out. There on the red dirt they’d put down firewood and then the bodies, piled and chopped up, and set fire to them using gasoline, until nothing was left but the charred bones and metallic objects like belt buckles and pants buttons. Witnesses who’ve sworn to having seen other mass graves like these—but who have not been able to reveal their locations—recount having perceived the odor of chemicals there that could be used to hasten the bodies’ incineration.

In onecamp a site was found that contained firewood and incinerated bone remains. We know from survivor testimonies that the CJNG used fire to get rid of thosewho did not obey or were of no use to the criminal organization.

The getaway

According to the story Luis told the Jalisco public prosecutor’s office, days later El Sapo got on the radio and announced “So now who wants a vacation, you sons-of-bitches?” Luis thought he’d finally found the moment he’d been waiting for. The process of degradation and being with those people had been endless. “I’m going to be free.” El Cholo ordered them to form two lines and gave each of them 2000 pesos. After nightfall, they took them down in groups of fifteen.

—“They were going to drop us off in Tala, but the situation was too hot; there were too many cops. We went to a gas station where the army was positioned. Because I’d been such a standout, a lot of them didn’t want to let go of me. The army guys didn’t stop us or ask us anything. There’s a hotel there; I went and checked in. I managed to take a shower so a cab driver would trust me and I could escape. When I got to the hotel all the rooms were filling up; we paid with the money they’d given us. I showered and wiped down my clothes with a wet rag. Everybody was knocking on the door, determined to have a beer in the bar. I was planning on cutting out as soon as they fell asleep, but they started doing meth the woman in charge sold them (…) As they partied on, I grabbed my bag, cut out, grabbed a taxi and contacted a relative that lives abroad. I told him everything that had happened, that I couldn’t go back, that they’d kill me wherever they spotted me, that someone had to help me escape.

“Then it came out in the news that someone like me got up the courage to speak out and I said to myself: my goal with getting out of there was to try to bring some peace and tranquility to the people that hadn’t found their loved ones, the ones I saw them burn up, when no one in their families knew how they died or how they disappeared. I’m going to take the risk and tell my story.”

The ones that came back from this hell were provided with protective measures for coming forward against members of Mexico’s most powerful cartel. With all that, they still had to flee; they changed their identities and were never heard from again. The Jalisco state government never revealed who it was that had been incinerated, whose remains were found at the camps. Nor did it undertake any more search operations for more clandestine mass graves in the area or try to free more young people in these forced-labor “recruitment” camps.

Today the cartels continue to conscript “recruits” and control the land. Both in the south of Jalisco and along the border with Michoacán there are relatives of the disappeared who have anonymously testified they hold evidence of family members being carried off to forced labor in drug labs or poppy fields. Residents of the Tala area know that the hell to which relatives and acquaintances have been condemned isn’t underneath them. It’s above, at the very summit of the sierra. They know this but say nothing.

From 2006 to date, the Mexican government has received complaints about the disappearance of more than 40,000 individuals.

This report is part of the A dónde van los desaparecidos / Quinto Elemento Lab project. A preliminary version was published (in Spanish) as a podcast at Así como suena, under the title Los desaparecidos de Jalisco. Listen here: http://asicomosuena.mx/?#/shows/1/play/361

Súmate a la comunidad de Quinto Elemento Lab

Suscríbete a nuestro newsletter

El Quinto Elemento, Laboratorio de Investigación e Innovación Periodística A.C. es una organización sin fines de lucro.

Dirección postal

Medellín 33

Colonia Roma Norte

CDMX, C.P. 06700